Guidance

Advice to the Gambling Commission on a statutory levy

A paper by the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling advising the Gambling Commission on a statutory levy

Section 3: The case for change

Gambling related harm has serious negative consequences to individuals and society – activity to reduce it requires adequate funding

There is a consensus from evidence across many jurisdictions that gambling is not a risk-free product. It has the potential to cause significant harms 23,24,25. There is an increasing evidence base on the relationship between suicide ideation and suicides and gambling26. Gambling is a growing activity amongst children and young people27,28. Other negative associations have emerged between gambling and domestic violence,29 gambling and debt30 and gambling and crime31. These harms are wide ranging, with detrimental impacts on resources, relationships and health32. Moreover, people do not need to be gamblers themselves to be affected by gambling harms: parents bereaved by suicide; partners experiencing stress, anxiety and relationship breakdown; children neglected either emotionally or financially by parents gambling are some of the more severe examples of gambling harms33.

Gambling harms are also likely to affect a broader proportion of the population that previously acknowledged through prevalence surveys. Research in Victoria, Australia estimated that 85 percent of gambling harms occur amongst low to moderate risk gamblers34. In Australia and New Zealand the harms from gambling are estimated to be of similar magnitude to alcohol misuse and dependence, or major depressive disorder35. These studies suggest that the real scale of gambling-related harms are downplayed by the traditional approach of referring only to problem gambling rates.

The rising extent, accessibility and exposure to gambling have raised concerns about impact, particularly on children and young people who are growing up in a digital environment36,37, where gambling activities are available at any time. Recent research has shown that those aged 17 to 20 years are particularly vulnerable to the onset of gambling problems, with the rates of problem gambling increasing more than three-fold between the ages of 17 and 2038. In light of the high risk of harm, researchers suggest that precautionary action should be taken.

The current funding model is no longer fit for purpose

In the UK, funding for research, prevention and treatment for gambling has been provided primarily through voluntary donations to a nominated charity: currently GambleAware. These contributions are distributed to a wide range of third sector, academic institutions and two NHS providers. The target amount to be raised each year in voluntary donations is £10 million, representing 0.1 percent of Gross Gambling Yield (GGY) In 2018/19, GambleAware received £9.6 million in donations39. Just over half of this was spent on treatment.

The current arrangements are distinct to Great Britain but internationally, there is no standard mechanism for funding research, prevention and treatment. New Zealand as well as some Australian states such as New South Wales and Victoria use a hypothecated tax40. Canadian provinces tend to have high levels of expenditure addressing gambling harm paid for out of general taxation; but all have specific proportions of their total revenue derived from specific taxes on gambling. In Europe, Spain is an example where general tax revenue funds almost all spending on treatment, prevention and research. In other countries, state monopolists may use part of their profits. In Denmark, the regulator has responsibility for funding public health campaigns.

A recent report from the International Association of Gaming Regulators suggests that two thirds of jurisdictions surveyed now require mandatory contributions to address gambling harms41. This suggests that Great Britain’s current reliance on a voluntary system is out of step with international regulatory trends.

As the final review of progress of the National Responsible Gambling Strategy during 2016-2019 showed, there was little evidence of systematic progress towards reducing harms42. This report also noted the need for increased funding for both prevention and treatment in order to address harms.

Any arrangement based on voluntary contributions is not a viable long-term model for funding research, prevention and treatment of gambling harms. here are a number of reasons for this which draw on evidence from the UK as well as other jurisdictions:

(i) There is a lack of transparency and perception of a lack of independence from industry

Gambling harms are now widely recognised as a public health issue, and yet funding for research to improve understanding, prevention and treatment lies outside established infrastructures and are not currently subject to the same principles of transparency and accountability as other areas of public health research or service provision43.

Despite improvements in research governance protocols and procedures around initiatives funded through voluntary contributions, the voluntary nature of arrangements gives rise to the perception that control of funding streams is placed principally with the industry, who may choose to fund particular projects, withdraw funding or alter their quotas at any time.

The recent announcement by the Betting and Gaming Council (BGC) is the most recent high profile example of this trend44. In June 2020, the BGC, acting on behalf of the so called ‘big five’ gambling operators, pledged that the £100 million of funds promised to the Chadlington Committee would instead be donated to GambleAware. Some weeks following this, BGC announced that the Chadlington Committee would receive £100k.

This shift in the destination of funding highlights concerns about industry influence within a voluntary system. These concerns were summarised by a group of UK based academics in an open letter to Secretaries of State45.

These negative perceptions, resulting from the way the voluntary system currently operates, are deeply ingrained, persistent and influence public confidence in the system at a time when trust in the gambling industry is declining46 and public concern about gambling harms is increasing.

(ii) There is a lack of equity across operators

Any form of gambling has the potential to lead to harm. All those responsible for providing gambling products to the public (either directly or indirectly) have a responsibility to invest in the prevention and treatment of those harms.

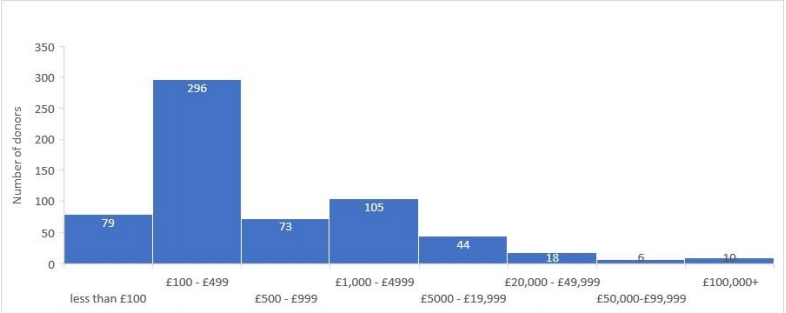

A voluntary system creates inequity between providers. In 2018/19 64 percent of licenced gambling operators made contributions to the voluntary system47. In the financial year 2019/20 over 600 individual donations have been made to GambleAware, ten companies donated 63 percent of all funds (see Figure 1). The highest single donation was for £552,000. 70 percent of all donations were for an amount of less than £1000; some donated only £10. The median donation was £25048. This distribution of contributions indicates a high degree of relative ‘free riding’ within the current system.

Figure 1: Number and value of donations to GambleAware for the

financial year 2019/2049

(iii) Funding for research and prevention is neither sustainable nor sufficient

Dealing with gambling harms as a public health issue requires significant sustained investment in research and prevention services. Voluntary systems are, by their nature, more unpredictable. Year-on-year there is no certainty of a dedicated funding stream required to establish research funds or effective prevention strategies.

Despite concerted efforts, GambleAware has until now found it challenging to reach the current annual target of 0.1 percent for voluntary contributions. Without recent intervention from the Commission during the Covid-19 pandemic, its ability to continue funding established projects was at risk50. For many years, voluntary donations to GambleAware slowly increased but have remained below the target. We have yet to see how and when the recent pledge of significant additional funds is delivered.

Other health harming behaviours such as substance abuse and misuse, including alcohol, have received significant health research funding. To date, gambling has not. The legislative framing in the Gambling Act 2005 of gambling as a leisure pursuit, means gambling has not, until recently, been considered a specific responsibility of government health departments. As such, research and prevention activities for gambling have struggled to compete against more widely recognised health harms among public health and social research funders.

Table 1 illustrates the number of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Research Council UK (RCUK) funded studies related to alcohol and gambling and the disparity between them.

Table 1: NIHR and RCUK funding for alcohol and gambling

| Funder | Alcohol research studies | Gambling research studies |

|---|---|---|

| NIHR (since 1991) | 151 | 1 |

| RCUK51 (since 2006) | 540 | 2252 |

(iv) Treatment services are not comprehensive, nor sufficiently integrated with the NHS

Despite a growing evidence base on treatment effectiveness53,54 (see Appendix 1 for examples of psychological treatments) the availability of treatment services for people who have experienced harm and their families is currently very limited. In 2017, less than three percent of the estimated 340,000 high risk problem gamblers in Great Britain received treatment, without reference to a further half a million moderate risk gamblers identified through recent surveys55. By contrast, recent (England only) estimates suggest that 18 percent of individuals with alcohol addictions are in receipt of commissioned services56.

There are only two centres jointly funded by the NHS and GambleAware and only two third sector residential centres provided by Gordon Moody. GamCare provides treatment services via a national network made up of organisations including Beacon Counselling Trust, Aquarius, the Addiction Recovery Agency, and many others57. GamCare also provides a National Helpline, which has been in operation 24-hours a day since October 2019. Other support services provided by the third sector include organisations such as Gamblers Anonymous58, Adfam59, Gambling with Lives60, YGAM61, Fast Forward62 and many more63,64.

In addition to specialist NHS and third sector provision, a fully integrated treatment service would require GB-wide primary care-based services. Early identification, intervention and onward referral of those who need treatment can only be successful if GP practices are involved. There are currently no NHS primary care-led services for those harmed from gambling or their families in Great Britain. By contrast, individuals with drug and alcohol related problems are served by a national primary care led scheme. Scotland and Wales are piloting a number of whole systems approaches which will provide new evidence on integrated services and their success in improving access to local services65,66. This requires sustainable, long-term investment.

These are the key reasons why we propose that a voluntary system to fund prevention and treatment of gambling harms is no longer fit for purpose. A statutory levy would be able to address many of the issues surrounding transparency, independence, equity and sustainability and public confidence. It would also have the potential to raise significantly greater levels of funding needed to address gambling harms across Great Britain.

References

23 Measuring gambling-related harms, a framework for action (opens in new tab), Wardle et al, July 2018

24 Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms (opens in new tab), Langham et al, BMC Public Health, 2016

25 Harms associated with gambling: abbreviated systematic review protocol (opens in new tab), Benyon et al, Systematic Reviews, June 2020

26 Gambling-related research – summary (opens in new tab), Heather Wardle, Sally McManus, Simon Dymond, Ann John, July 2019

27 Young people and gambling survey 2019, Gambling Commission, October 2019. 11 to 16-year olds who gamble are six times more likely to participate in gambling than smoking, seven times more likely to participate in gambling than using drugs, and four times more likely to participate in gambling than use alcohol than non-gamblers.

28 Loot boxes are again linked to problem gambling: Results of a replication study (opens in new tab), Zendle et al, PLOS One, March 2019

29 Systematic Review of Problem Gambling and Intimate Partner Violence (opens in new tab). Trauma Violence Abuse, Dowling et al, 2016 – This review of 14 studies found a significant relationship between problem gambling and intimate partner violence

30 Gambling and debt: the hidden impacts on family and work life (opens in new tab), Downs and Woolrych, 2010

31 Gambling among offenders: Results from an Australian survey (opens in new tab). International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, Lahn, J. 2005. The relationship of problem gambling to criminal behavior in a sample of Canadian male federal offenders (opens in new tab). Journal of Gambling Studies, Turner et al, 2009

32 Problem Gamblers: characteristics of individuals who offend to finance gambling (opens in new tab), International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, Roberts et al, 2019

33 Measuring gambling-related harms, a framework for action (opens in new tab), Wardle et al, July 2018

34 Victoria Responsible Gambling Foundation (opens in new tab) – Gambling harm in Victoria

35 Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm (opens in new tab), Wardle, Reith, Langham, BMJ, May 2019

36 Reducing online harms, ABSG, July 2019

37 (Page 78) Gambling Harm - Time for Action (opens in new tab), House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry July 2020

38 Gambling and problem gambling among young adults: Insights from a longitudinal study of parents and children (opens in new tab), David Forrest and Ian McHale, August 2018

39 GambleAware, Annual Report (opens in new tab), 2017/18. 2019/20 figures not yet available

40 Problem Gambling (opens in new tab), Department of Internal Affairs, New Zealand Government

41 Gambling Regulation – Global Developments 2018-19 (opens in new tab), IAGR, November 2019

42 Final Progress Report: National Responsible Gambling Strategy 2016-2019 (opens in new tab), Responsible Gambling Strategy Board, March 2019

43 With a few notable exceptions - e.g. Funding research from NIHR and other funding bodies, two NHS part funded clinics in the National NHS clinic in London, and the NHS part funded clinic in Leeds

44 News update (opens in new tab), Betting and Gaming Council, June 2020

46 (Page 47), Gambling participation in 2018, Behaviour, awareness and attitudes. Gambling Commission. February 2019

47 This figure is based on 1,766 out of 2,753 active operators. This figure is subject to the following caveats – It is based on the date the contribution was made, and not the date the operator reported the contribution to the Gambling Commission. It is based on the average number of active operators over the period 01/04/18 - 31/04/19. When a group company has made a contribution, all operators under that group are counted as making a contribution. It does not take into account operators where a trade body has made a donation on their behalf.

48 2019/20 supporters (opens in new tab), GambleAware

49 GambleAware data on donations received

50 Gambling Commission directs £9m to boost resilience of gambling harm treatment services during Covid-19, Gambling Commission, April 2020

51 RCUK includes AHRC, BBSRC, EPSRC, ESRC, Innovate UK, MRC, NC3RS, NERC, STFC, UKRI

52 NIHR - https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/; (opens in new tab) RCUK - https://gtr.ukri.org/ (opens in new tab) - 71 identified on basic search but on review most not related to gambling and only 22 include ‘gambling’ in the abstract

53 Effectiveness of problem gambling interventions in a service setting: a protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial (opens in new tab), Abbott et al, 2017

54 Rapid evidence review of evidence-based treatment for Gambling Disorder in Britain (opens in new tab), Bowden-Jones, Drummond & Thomas, December, 2016

55 Health Survey for England 2018 (opens in new tab), NHS Digital, December 2019

56 Adult substance misuse treatment statistics 2018 to 2019 (opens in new tab), National Statistics, Public Health England, November 2019

57 Correct at time of writing

58 Gamblers Anonymous (opens in new tab) - website

59 Adfam (opens in new tab) - website

60 Gambling with Lives (opens in new tab) - website

61 YGAM (opens in new tab) - website

62 Fast Forward (opens in new tab) - website

63 List of organisations to which operators may direct their annual financial contribution for gambling research, prevention and treatment, Gambling Commission

64 Updated map of actions (opens in new tab), National Strategy to Reduce gambling Harms, July 2020

65 Toward a public health approach for gambling-related harm: a scoping document (opens in new tab), ScotPHN, Michelle Gillies, August 2016

66 Gambling with our health (opens in new tab), Chief Medical Officer for Wales, Annual Report 2016/17

Advice to the Gambling Commission on a statutory levy: Background Next section

Advice to the Gambling Commission on a statutory levy: What could a statutory levy achieve?

Last updated: 28 September 2023

Show updates to this content

Formatting issues corrected only.