- Print the full document

- Save the page as a HTML document to your device

- Save the page as a PDF file

- Bookmark it - it will always be the latest version of this document

This box is not visible in the printed version.

Advice to the Gambling Commission on a statutory levy

A paper by the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling advising the Gambling Commission on a statutory levy

Published: 1 September 2020

Last updated: 19 August 2021

This version was printed or saved on: 2 February 2026

Online version: https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/guidance/advice-to-the-gambling-commission-on-a-statutory-levy

Executive Summary

This paper sets out the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling’s advice on the most effective approach to funding activities to reduce gambling harms. The advice contains three main recommendations and sets out why reform of the current approach is needed. Our three main recommendations are:

- Establish a statutory levy on all gambling operators

- Set the levy at one percent, with a review after two years

- Establish an independent Safer Gambling Levy Board to oversee the distribution of funds.

Change in the landscape of gambling harms requires a new approach to research, prevention and treatment services. Gambling-related harm is a serious issue – it has negative impacts on large numbers of people. The impacts are now recognised as being far more widespread than the estimated 340,000 people classified as problem gamblers. Addressing these harms requires adequate and sustainable funding. Despite efforts by the Gambling Commission and other stakeholders to improve the current voluntary system, it remains not fit for purpose. Its weaknesses include:

- A lack of transparency

- A lack of equity across operators

- A record of insufficient funding

- Voluntary funding that is unpredictable and creates barriers to distributing funds to where they can have the most impact – such as the NHS.

We recommend that a statutory levy, set at one percent of gross gambling yield (GGY) replaces the voluntary system. This would provide a sustainable basis for partnerships to deliver effective research, prevention and treatment activities and open up a wider range of distribution and partnership opportunities.

We recognise that these recommendations are not without challenges, and the impact of Covid-19 on the industry has yet to be quantified. They would, however, allow a greater pace of progress to reducing gambling harms, and would create a fairer and more efficient approach that would significantly benefit those affected by harms. Our advice includes recommendations on enabling actions to assist this transition.

Section 1: Introduction

This paper sets out advice from the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling (ABSG) on the case for a statutory levy1. ABSG previously outlined its support for a statutory levy to enable the delivery of effective prevention and treatment of gambling harms across Great Britain2.

This advice reiterates our view that a statutory levy is the most effective option to fund activity to reduce gambling harms. It outlines why a statutory levy is necessary, the evidence supporting this, and the type of levy required. We also discuss challenges of implementation and recommends transitional options to ensure continuity of treatment support and investment in prevention and independent research whilst the mechanics of a levy are established.

A levy would help accelerate progress in delivering the National Strategy to Reduce Gambling Harms. Key priorities are identified in our Progress Report on the Strategy published in June 20203. We welcome the endorsements in favour of a statutory levy which have emerged this year, notably in reports from the All Parliamentary Group on Gambling-Related Harm and House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry4.

The paper is structured as follows:

- Section 2 – provides background context

- Section 3 – sets out the case for change

- Section 4 – outlines benefits that a statutory levy could help achieve

- Section 5 – explains challenges to implementation

- Section 6 – considers short-term enablers of change

- Section 7 – provides conclusions.

1 In November 2019, the Gambling Commission asked ABSG for their advice on the case for a statutory levy. A first draft of this advice was submitted in January 2020. In July 2020, the Gambling Commission asked ABSG to review the draft in light of recent developments – including the Covid-19 pandemic and parliamentary reports on gambling from the House of Lords, the All Parliamentary Group on Gambling-Related Harm and the Public Accounts Committee.

2 (Page 26) Two years on: progress delivering the National Responsible Gambling Strategy (PDF), Responsible Gambling Strategy Board, May 2018. (Page 3) The Responsible Gambling Strategy Board’s advice on the National Strategy to Reduce Gambling Harms 2019-2022 (PDF), Responsible Gambling Strategy Board, February 2019

3 Progress report, Advisory Board for Safer Gambling, June 2020

4 Online Gambling Harm Inquiry – Interim Report, Report from the Gambling Related Harm All-Party Parliamentary Group, November 2019. This link was available at the time of publishing but is no longer available.

Section 2: Background

The provision, promotion and participation in gambling has changed significantly in the last five years. More forms of gambling are available in Britain than ever before. The most recent survey results (England only) published by NHS Digital show that 54 percent of adults had participated in some form of gambling during the previous twelve months5. Participation of itself is not an indicator of harm, but it does increase exposure to the risks of harm to a greater number of people6,7. There is evidence that those from disadvantaged communities see gambling as a solution to debt or financial hardship8,9. This means that gambling is likely to contribute to health,income and social inequalities across Great Britain10.

Great Britain has the largest regulated market for online gambling in the world11,12,13. Online activity makes up 37 percent of total market share14, Between 2009 and 2019, operator yield from online gambling activity increased from £1billion to £5.3billion15. Since 2015, advertising spend by the industry has increased by 24 percent and 45 percent of total advertising spend is now online16. These shifts to more widely accessible markets have given rise to increased political scrutiny17 and public concern about the impact of gambling activities, particularly on children and young people. Since the start of the Covid-19 outbreak, Gambling Commission published data shows a shift towards online gambling, a trend which may persist in the longer-term18.

Finally, there have been major policy changes to the provision of treatment for gambling harms across Great Britain, with increasing recognition of gambling as a public health concern in Scotland19, Wales20 and England21. For example, in 2019, the NHS England Long Term Plan identified, for the first time, the need for an expansion of national provision of treatment for those harmed by gambling. There has been subsequent announcement of plans to create up to 14 new NHS treatment centres across England22.

Taken together, these changes require a new approach to the provision of funding for treatment, prevention and research. The current system of voluntary donations does not provide a sufficient quantity of funds upon which to develop a sustainable, integrated approach to reducing gambling harms. Addressing gambling harms as a public health concern requires a different level of investment.

5 Health Survey for England 2018 (opens in new tab), NHS Digital, December 2019

6 The changing epidemiology of gambling disorder and gambling related harm: public health implications, Abbott, 2020

7 Measuring the burden of gambling harm in New Zealand (opens in new tab), Browne et al, May 2017

8 Toward a public health approach for gambling-related harm: a scoping document (opens in new tab), Gillies, M, Scottish Public Health Network, August 2016

9 Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm, Wardle (opens in new tab), Reith, Langham, BMJ, May 2019

10 Psychological risk factors in disordered gambling: A descriptive systematic overview of vulnerable populations (opens in new tab), Sharman et al, 2019

11 Review of online gambling, Gambling Commission, March 2018

12 Gambling Industry Statistics, Gambling Commission, May 2020

13 Gambling regulation: problem gambling and protecting vulnerable people (opens in new tab), National Audit Office, February 2020

14 Industry statistics – April 2016 to March 2019, Gambling Commission, November 2019

15 (p.36) Gambling regulation: problem gambling and protecting vulnerable people (opens in new tab), National Audit Office, February 2020

16 Interim synthesis report – The effect of gambling marketing and advertising on children, young people and vulnerable adults (opens in new tab), Ipsos MORI, July 2019

17 Online Gambling Harm Inquiry – Interim Report, Report from the Gambling Related Harm All-Party Parliamentary Group (opens in new tab), November 2019. This link was available at the time of publishing but is no longer available.

18 Covid-19 and its impact on gambling – what we know so far (Updated July 2020), Gambling Commission, July 2020

19 Toward a public health approach for gambling-related harm: a scoping document (opens in new tab), Gillies, M, Scottish Public Health Network, August 2016

20 Gambling as a public health issue in Wales (opens in new tab), Rogers et al, Bangor University, 2019

21 The NHS Long Term Plan (opens in new tab), NHS, January 2019 (para 2.36)

22 NHS to launch young people’s gambling addiction service (opens in new tab), NHS, June 2019

Section 3: The case for change

Gambling related harm has serious negative consequences to individuals and society – activity to reduce it requires adequate funding

There is a consensus from evidence across many jurisdictions that gambling is not a risk-free product. It has the potential to cause significant harms 23,24,25. There is an increasing evidence base on the relationship between suicide ideation and suicides and gambling26. Gambling is a growing activity amongst children and young people27,28. Other negative associations have emerged between gambling and domestic violence,29 gambling and debt30 and gambling and crime31. These harms are wide ranging, with detrimental impacts on resources, relationships and health32. Moreover, people do not need to be gamblers themselves to be affected by gambling harms: parents bereaved by suicide; partners experiencing stress, anxiety and relationship breakdown; children neglected either emotionally or financially by parents gambling are some of the more severe examples of gambling harms33.

Gambling harms are also likely to affect a broader proportion of the population that previously acknowledged through prevalence surveys. Research in Victoria, Australia estimated that 85 percent of gambling harms occur amongst low to moderate risk gamblers34. In Australia and New Zealand the harms from gambling are estimated to be of similar magnitude to alcohol misuse and dependence, or major depressive disorder35. These studies suggest that the real scale of gambling-related harms are downplayed by the traditional approach of referring only to problem gambling rates.

The rising extent, accessibility and exposure to gambling have raised concerns about impact, particularly on children and young people who are growing up in a digital environment36,37, where gambling activities are available at any time. Recent research has shown that those aged 17 to 20 years are particularly vulnerable to the onset of gambling problems, with the rates of problem gambling increasing more than three-fold between the ages of 17 and 2038. In light of the high risk of harm, researchers suggest that precautionary action should be taken.

The current funding model is no longer fit for purpose

In the UK, funding for research, prevention and treatment for gambling has been provided primarily through voluntary donations to a nominated charity: currently GambleAware. These contributions are distributed to a wide range of third sector, academic institutions and two NHS providers. The target amount to be raised each year in voluntary donations is £10 million, representing 0.1 percent of Gross Gambling Yield (GGY) In 2018/19, GambleAware received £9.6 million in donations39. Just over half of this was spent on treatment.

The current arrangements are distinct to Great Britain but internationally, there is no standard mechanism for funding research, prevention and treatment. New Zealand as well as some Australian states such as New South Wales and Victoria use a hypothecated tax40. Canadian provinces tend to have high levels of expenditure addressing gambling harm paid for out of general taxation; but all have specific proportions of their total revenue derived from specific taxes on gambling. In Europe, Spain is an example where general tax revenue funds almost all spending on treatment, prevention and research. In other countries, state monopolists may use part of their profits. In Denmark, the regulator has responsibility for funding public health campaigns.

A recent report from the International Association of Gaming Regulators suggests that two thirds of jurisdictions surveyed now require mandatory contributions to address gambling harms41. This suggests that Great Britain’s current reliance on a voluntary system is out of step with international regulatory trends.

As the final review of progress of the National Responsible Gambling Strategy during 2016-2019 showed, there was little evidence of systematic progress towards reducing harms42. This report also noted the need for increased funding for both prevention and treatment in order to address harms.

Any arrangement based on voluntary contributions is not a viable long-term model for funding research, prevention and treatment of gambling harms. here are a number of reasons for this which draw on evidence from the UK as well as other jurisdictions:

(i) There is a lack of transparency and perception of a lack of independence from industry

Gambling harms are now widely recognised as a public health issue, and yet funding for research to improve understanding, prevention and treatment lies outside established infrastructures and are not currently subject to the same principles of transparency and accountability as other areas of public health research or service provision43.

Despite improvements in research governance protocols and procedures around initiatives funded through voluntary contributions, the voluntary nature of arrangements gives rise to the perception that control of funding streams is placed principally with the industry, who may choose to fund particular projects, withdraw funding or alter their quotas at any time.

The recent announcement by the Betting and Gaming Council (BGC) is the most recent high profile example of this trend44. In June 2020, the BGC, acting on behalf of the so called ‘big five’ gambling operators, pledged that the £100 million of funds promised to the Chadlington Committee would instead be donated to GambleAware. Some weeks following this, BGC announced that the Chadlington Committee would receive £100k.

This shift in the destination of funding highlights concerns about industry influence within a voluntary system. These concerns were summarised by a group of UK based academics in an open letter to Secretaries of State45.

These negative perceptions, resulting from the way the voluntary system currently operates, are deeply ingrained, persistent and influence public confidence in the system at a time when trust in the gambling industry is declining46 and public concern about gambling harms is increasing.

(ii) There is a lack of equity across operators

Any form of gambling has the potential to lead to harm. All those responsible for providing gambling products to the public (either directly or indirectly) have a responsibility to invest in the prevention and treatment of those harms.

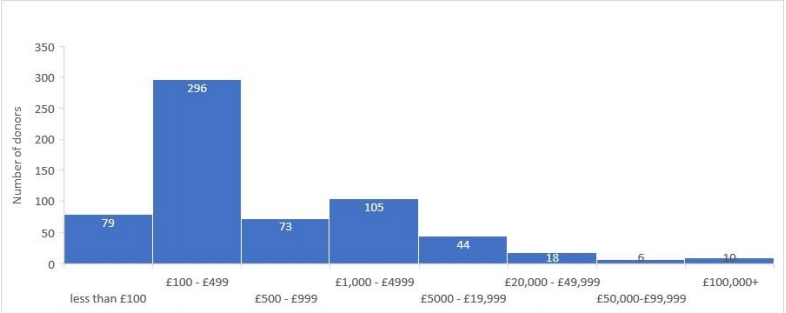

A voluntary system creates inequity between providers. In 2018/19 64 percent of licenced gambling operators made contributions to the voluntary system47. In the financial year 2019/20 over 600 individual donations have been made to GambleAware, ten companies donated 63 percent of all funds (see Figure 1). The highest single donation was for £552,000. 70 percent of all donations were for an amount of less than £1000; some donated only £10. The median donation was £25048. This distribution of contributions indicates a high degree of relative ‘free riding’ within the current system.

Figure 1: Number and value of donations to GambleAware for the

financial year 2019/2049

(iii) Funding for research and prevention is neither sustainable nor sufficient

Dealing with gambling harms as a public health issue requires significant sustained investment in research and prevention services. Voluntary systems are, by their nature, more unpredictable. Year-on-year there is no certainty of a dedicated funding stream required to establish research funds or effective prevention strategies.

Despite concerted efforts, GambleAware has until now found it challenging to reach the current annual target of 0.1 percent for voluntary contributions. Without recent intervention from the Commission during the Covid-19 pandemic, its ability to continue funding established projects was at risk50. For many years, voluntary donations to GambleAware slowly increased but have remained below the target. We have yet to see how and when the recent pledge of significant additional funds is delivered.

Other health harming behaviours such as substance abuse and misuse, including alcohol, have received significant health research funding. To date, gambling has not. The legislative framing in the Gambling Act 2005 of gambling as a leisure pursuit, means gambling has not, until recently, been considered a specific responsibility of government health departments. As such, research and prevention activities for gambling have struggled to compete against more widely recognised health harms among public health and social research funders.

Table 1 illustrates the number of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Research Council UK (RCUK) funded studies related to alcohol and gambling and the disparity between them.

Table 1: NIHR and RCUK funding for alcohol and gambling

| Funder | Alcohol research studies | Gambling research studies |

|---|---|---|

| NIHR (since 1991) | 151 | 1 |

| RCUK51 (since 2006) | 540 | 2252 |

(iv) Treatment services are not comprehensive, nor sufficiently integrated with the NHS

Despite a growing evidence base on treatment effectiveness53,54 (see Appendix 1 for examples of psychological treatments) the availability of treatment services for people who have experienced harm and their families is currently very limited. In 2017, less than three percent of the estimated 340,000 high risk problem gamblers in Great Britain received treatment, without reference to a further half a million moderate risk gamblers identified through recent surveys55. By contrast, recent (England only) estimates suggest that 18 percent of individuals with alcohol addictions are in receipt of commissioned services56.

There are only two centres jointly funded by the NHS and GambleAware and only two third sector residential centres provided by Gordon Moody. GamCare provides treatment services via a national network made up of organisations including Beacon Counselling Trust, Aquarius, the Addiction Recovery Agency, and many others57. GamCare also provides a National Helpline, which has been in operation 24-hours a day since October 2019. Other support services provided by the third sector include organisations such as Gamblers Anonymous58, Adfam59, Gambling with Lives60, YGAM61, Fast Forward62 and many more63,64.

In addition to specialist NHS and third sector provision, a fully integrated treatment service would require GB-wide primary care-based services. Early identification, intervention and onward referral of those who need treatment can only be successful if GP practices are involved. There are currently no NHS primary care-led services for those harmed from gambling or their families in Great Britain. By contrast, individuals with drug and alcohol related problems are served by a national primary care led scheme. Scotland and Wales are piloting a number of whole systems approaches which will provide new evidence on integrated services and their success in improving access to local services65,66. This requires sustainable, long-term investment.

These are the key reasons why we propose that a voluntary system to fund prevention and treatment of gambling harms is no longer fit for purpose. A statutory levy would be able to address many of the issues surrounding transparency, independence, equity and sustainability and public confidence. It would also have the potential to raise significantly greater levels of funding needed to address gambling harms across Great Britain.

23 Measuring gambling-related harms, a framework for action (opens in new tab), Wardle et al, July 2018

24 Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms (opens in new tab), Langham et al, BMC Public Health, 2016

25 Harms associated with gambling: abbreviated systematic review protocol (opens in new tab), Benyon et al, Systematic Reviews, June 2020

26 Gambling-related research – summary (opens in new tab), Heather Wardle, Sally McManus, Simon Dymond, Ann John, July 2019

27 Young people and gambling survey 2019, Gambling Commission, October 2019. 11 to 16-year olds who gamble are six times more likely to participate in gambling than smoking, seven times more likely to participate in gambling than using drugs, and four times more likely to participate in gambling than use alcohol than non-gamblers.

28 Loot boxes are again linked to problem gambling: Results of a replication study (opens in new tab), Zendle et al, PLOS One, March 2019

29 Systematic Review of Problem Gambling and Intimate Partner Violence (opens in new tab). Trauma Violence Abuse, Dowling et al, 2016 – This review of 14 studies found a significant relationship between problem gambling and intimate partner violence

30 Gambling and debt: the hidden impacts on family and work life (opens in new tab), Downs and Woolrych, 2010

31 Gambling among offenders: Results from an Australian survey (opens in new tab). International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, Lahn, J. 2005. The relationship of problem gambling to criminal behavior in a sample of Canadian male federal offenders (opens in new tab). Journal of Gambling Studies, Turner et al, 2009

32 Problem Gamblers: characteristics of individuals who offend to finance gambling (opens in new tab), International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, Roberts et al, 2019

33 Measuring gambling-related harms, a framework for action (opens in new tab), Wardle et al, July 2018

34 Victoria Responsible Gambling Foundation (opens in new tab) – Gambling harm in Victoria

35 Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm (opens in new tab), Wardle, Reith, Langham, BMJ, May 2019

36 Reducing online harms, ABSG, July 2019

37 (Page 78) Gambling Harm - Time for Action (opens in new tab), House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry July 2020

38 Gambling and problem gambling among young adults: Insights from a longitudinal study of parents and children (opens in new tab), David Forrest and Ian McHale, August 2018

39 GambleAware, Annual Report (opens in new tab), 2017/18. 2019/20 figures not yet available

40 Problem Gambling (opens in new tab), Department of Internal Affairs, New Zealand Government

41 Gambling Regulation – Global Developments 2018-19 (opens in new tab), IAGR, November 2019

42 Final Progress Report: National Responsible Gambling Strategy 2016-2019 (opens in new tab), Responsible Gambling Strategy Board, March 2019

43 With a few notable exceptions - e.g. Funding research from NIHR and other funding bodies, two NHS part funded clinics in the National NHS clinic in London, and the NHS part funded clinic in Leeds

44 News update (opens in new tab), Betting and Gaming Council, June 2020

46 (Page 47), Gambling participation in 2018, Behaviour, awareness and attitudes. Gambling Commission. February 2019

47 This figure is based on 1,766 out of 2,753 active operators. This figure is subject to the following caveats – It is based on the date the contribution was made, and not the date the operator reported the contribution to the Gambling Commission. It is based on the average number of active operators over the period 01/04/18 - 31/04/19. When a group company has made a contribution, all operators under that group are counted as making a contribution. It does not take into account operators where a trade body has made a donation on their behalf.

48 2019/20 supporters (opens in new tab), GambleAware

49 GambleAware data on donations received

50 Gambling Commission directs £9m to boost resilience of gambling harm treatment services during Covid-19, Gambling Commission, April 2020

51 RCUK includes AHRC, BBSRC, EPSRC, ESRC, Innovate UK, MRC, NC3RS, NERC, STFC, UKRI

52 NIHR - https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/; (opens in new tab) RCUK - https://gtr.ukri.org/ (opens in new tab) - 71 identified on basic search but on review most not related to gambling and only 22 include ‘gambling’ in the abstract

53 Effectiveness of problem gambling interventions in a service setting: a protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial (opens in new tab), Abbott et al, 2017

54 Rapid evidence review of evidence-based treatment for Gambling Disorder in Britain (opens in new tab), Bowden-Jones, Drummond & Thomas, December, 2016

55 Health Survey for England 2018 (opens in new tab), NHS Digital, December 2019

56 Adult substance misuse treatment statistics 2018 to 2019 (opens in new tab), National Statistics, Public Health England, November 2019

57 Correct at time of writing

58 Gamblers Anonymous (opens in new tab) - website

59 Adfam (opens in new tab) - website

60 Gambling with Lives (opens in new tab) - website

61 YGAM (opens in new tab) - website

62 Fast Forward (opens in new tab) - website

63 List of organisations to which operators may direct their annual financial contribution for gambling research, prevention and treatment, Gambling Commission

64 Updated map of actions (opens in new tab), National Strategy to Reduce gambling Harms, July 2020

65 Toward a public health approach for gambling-related harm: a scoping document (opens in new tab), ScotPHN, Michelle Gillies, August 2016

66 Gambling with our health (opens in new tab), Chief Medical Officer for Wales, Annual Report 2016/17

Section 4: What could a statutory levy achieve?

In this section we outline the key benefits a levy could help achieve. This is not intended to be a full needs assessment. We outline key activities, processes and services which could be introduced with sustainable funding to illustrate the range of benefits which could be delivered.

A sustainable independent infrastructure for research

The current perception that gambling research is influenced by relationships with the gambling industry may be inhibiting both the acceptability of research findings and the attention of health researchers and health policymakers67,68,69. In both substance abuse and alcohol research, any direct funding for research from industry is seen as a clear conflict of interest70. There is strong evidence from other sectors showing that studies sponsored by industry are more likely to produce favourable results than non-industry funded studies71. However, this has not yet been examined for gambling research.

A statutory levy would help enable the creation of joint funding relationships with large health and social care funders such as NIHR, ESRC, Wellcome Trust and the Health Foundation. Mainstream health and social care funding partners have established processes for ethical approval, peer review, independent research oversight, and the involvement of those with lived experience in the design and delivery of research and frameworks for supporting early career researchers as standard. These governance and ethical frameworks provide quality assurance, ensure the involvement of experts by experience, and would offer new frameworks for gambling funded research programmes. These would, under a statutory levy, apply to all gambling related research, raising standards and attracting a wider pool of academic expertise into the sector.

Requirements of mainstream health and social care funding councils

- Ethical standards - Research undertaken within the NHS requires Health Research Authority (HRA) approval and compliance with ethical standards. The HRA is an executive non-departmental public body (NDPB) sponsored by the Department of Health, which provides robust ethical and legal governance, and supports transparency of NHS research - including a public register of all research.

- User involvement - Involvement of the public and other stakeholders in the co-production and delivery of research is fundamental to all NIHR activity, and UK Research and Innovation (which incorporates the seven Research Councils) requires researchers to broaden their focus on user involvement in research and engage more with under-represented groups72.

- Developing future research leaders - The NIHR and UKRI funders offer established pathways for the development of Early Career Researchers (ECR), for example the MRC supports the development of independent researchers through both fellowship schemes and MRC New Investigator Research Grants73, and the NIHR supports ECRs across fellowship schemes (NIHR Academy), project funding streams, research infrastructure (Applied Research Collaborations (ARCs) and research delivery (Clinical research Network (CRN))74.

A statutory levy would also drive innovation in research and development. The future of safer gambling will be increasingly tied to advances in technology, as developments in game design and communication infrastructure change the shape and nature of products and how they are marketed. These will potentially increase risks of harm for some but also provide opportunities for understanding consumer behaviour. Understanding these processes and how best to harness them for the protection of consumers will require significant, and independent, investment in data science combined with the skills of public health prevention experts.

A statutory levy would help generate these partnerships by enhancing the volume of resource in research and by creating a an independent research and development environment (see Appendix 2 for details of areas of research required and Appendix 3 for examples of research council funded studies in comparable areas).

A key objective in the National Strategy to Reduce Gambling Harms is the creation of an independent data repository, into which all operators will be mandated to submit their data for research purposes. Both the House of Lords75 and APPG76 Reports emphasise the importance of this work to understanding harms. There are precedents elsewhere for this approach. In France, the online gambling regulator, the Autorité de Regulation des Jeux en Ligne (ARJEL) mandates disclosure of transaction data and customer behaviour as part of the licence. This allows cross operator research to be conducted without direct funding77. In the UK, an initial scoping study by the University of Leeds provides details of how a data repository might be established and what this might cost. A statutory levy would allow the long-term investment necessary to create and maintain this world leading independent repository, which will be essential to building a credible and extensive evidence base on gambling harms78.

A sustainable funding stream for prevention

We know from other areas that preventative and public health interventions can reduce future costs associated with poor health. Predicted cost benefits suggest that £14.30 could be saved for every £1 invested79. The government’s across Great Britain recognise the importance of prevention to future population health and sustainability of the NHS80,81,82.

A statutory levy could make a significant contribution to a public health prevention approach. It would bring gambling research investment in line with other public health priorities that are important to preventing non-communicable disease (NCD) and reducing the health impacts of smoking, obesity and poor air quality. Unlike gambling, these areas have been key priorities within current prevention research funding streams including the UK Prevention Research Partnership funding initiative. This is a collaboration of funders (including the UKRI Research Councils, NIHR and charities) investing £50 million in 5-year primary NCD prevention research consortia and networks83, and the NIHR Public Health Research programme which invests £12 million each year in non-NHS prevention and population health research84.

A sustainable funding stream for treatment provision

A statutory levy would enable the funding of a wider range of effective and regulated treatment options, integrated within established NHS organisations working in partnership with the third sector.

Despite recent initiatives to expand helplines and treatment services, such as the helpline opening 24-hours a day85, there are large gaps in geographic availability and inequalities in access between different groups and communities. This can mean that those with the greatest need are least likely to get access to services.

The NHS England Long Term Plan proposes there is a need to create up to 14 centres that can offer a blend of treatment provision across England86. In addition to these specialist centres, adequate provision will require a system wide, intermediate integrated service (IIS) modelled on those existing in many areas of mental health. Based on successful initiatives for other addiction services87, these IIS would ideally be primary care led, multidisciplinary services able to identify, assess, case manage, prescribe and treat some gamblers, and refer on to other specialist treatment providers in the NHS and third sector.

These services would provide the bridge between third and specialist sectors. Only with such primary care involvement will services be able to deliver at scale and be able to provide routine screening and assessment and appropriate levels of support for those affected by gambling and their families88. There is a need to build on the learning from other services in areas of mental health to develop a tiered approach to service delivery, with different providers creating a more sustained, systematic delivery model. The forthcoming evidence review by Public Health England will be critical to the development of much anticipated NICE guidelines in 202189.

A sustainable funding stream for increasing workforce capacity

Increased treatment provision and prevention also means better awareness of gambling harms and likely increased demand for services as more individuals and their families seek help. The treatment system needs to be able to respond to this and build capacity, including through the primary care workforce, where currently one million individuals present for care each day.

All GPs need to be equipped with the skills, knowledge and support to identify, provide early intervention and appropriately signpost gamblers (through digital solutions as well as training programmes and support systems). In addition,there is a need to develop the skills of medical, nursing and mental health work force practitioners to identify gamblers who might present to accident and emergency, antenatal services, or mental health services. Some of this capacity building could be linked to existing training programmes such as the NHS Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, and other regional counselling service providers. Peer led training programmes at Recovery Colleges90 would also form an important part of this training, as would training delivered by third sector organisations with expertise in this area. All would require additional funding.

A sustainable approach that addresses the social and health costs to society

A recent UK review of the evidence on the social and health costs of gambling harm concluded that this was a new area for research with no published studies prior to the 1990s91. However, the report does provide a review of those countries that have carried out extensive analysis on the costs of gambling harms to society. The Australian Productivity Commission estimated that the social costs of gambling were between £2.5 and £4.4 billion per year, excluding costs in relation to health care services92. In Germany a study found that additional annual healthcare costs for their population of problem gamblers was £185 million93. Fully comparable costs calculations have yet to be made for Great Britain, but estimates of a range of social costs suggests these would be between £120 million to £1.1 billion.

67 Clear principles are needed for integrity in gambling research (opens in new tab), Livingstone and Adams, Addiction, June 2015

68 Gambling Research and Industry Funding (opens in new tab), Collins et al, Journal of Gambling Studies, 2019

69 Funding of gambling studies and its impact on research (opens in new tab), Nikkenden et al, Nordic Studies on Drugs and Alcohol, 2019

70 Funders must be wary of industry alliances (opens in new tab), Bauld, 2018

71 Industry sponsorship and research outcome (opens in new tab), Lundh, 2017

72 UKRI Vision for Public Engagement (opens in new tab), UKRI, 2019

73 Supporting early career researchers: (opens in new tab) The transition to independence, Medical Research Council

74 NIHR.ac.uk (opens in new tab)

75 Gambling Harm - Time for Action (opens in new tab), House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry July 2020

76 Report from the Gambling Related Harm All Party Parliamentary Group - Online Gambling Harm Inquiry, June 2020. This link was available at the time of publishing but is no longer available.

77 Typology of online lotteries and scratch games gamblers' behaviours: A multilevel latent class cluster analysis applied to player account-based gambling data (opens in new tab)Wiley online library October 2018

78 Independent Repository of gambling industry data – a scoping study (opens in new tab), Lomax, University of Leeds, August 2019

79 Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review (opens in new tab), Masters, Anwar, Collins et al, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2017

80 Toward a public health approach for gambling-related harm: a scoping document (opens in new tab), Gillies, et al, Scottish Public Health Network, August 2016

81 (Para 2.36, page 43) The NHS Long Term Plan (opens in new tab), NHS, January 2019

82 Gambling as a public health issue in Wales (opens in new tab), Rogers et al, Bangor University, 2019

83 Prevention research partnership UK (opens in new tab)

84 Funding programmes (opens in new tab), NIHR

85 National Gambling Helpline to Pilot 24-hour Service (opens in new tab), GamCare, August 2019

86 NHS to launch young people’s gambling addiction service (opens in new tab), NHS, June 2019

87 Gerada C, Tighe J, Betterton J, Barrett C. The Consultancy Liaison Addiction Service- the first five years of an integrated, primary care–based community drug and alcohol team. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 2000. The costs of a service based on this service are estimated at £15 million per year, although a full needs assessment for an IIS service for those affected by gambling would be required

88 Problem gambling and family violence in a population study (opens in new tab), Dowling et al, Journal of Behavioural Addictions, 2018

89 Gambling-related harms evidence review: scope (opens in new tab), Public Health England, October 2019

90 Recovery Colleges provide low cost support and training to people with a wide range of needs. Support and training courses are co-designed and led by people with lived experience and professionals. Services are online and face to face, individual and group. There are currently 81 Recovery Colleges in Great Britain, funded jointly by NHS and third sector organisations. The majority of them offer suicide prevention support and all have a strong focus on mental health and wellbeing. This is an example of an existing infrastructure that could be used to support individuals with gambling problems and their families.

91 Measuring Gambling-Related Harms: Methodologies & Data Scoping Study (opens in new tab). McDaid, Patel, London School of Economics and Political Science. 2019

92 (Page 48) A Productivity Commission Inquiry Report (opens in new tab), Australian Productivity Commission, 2010

93 The Effect of Online Gambling on Gambling Problems and Resulting Economic Health Costs in Germany (opens in new tab), Effertz et al, European Journal of Health Economics, 20182

Section 5: Challenges to implementation

Establishing the required level of funding, and the size of the levy

A primary benefit of a statutory levy is that it would substantially increase the volume of funding to provide effective research, education and treatment strategies to deliver a transformative change in approach to reducing harms.

Establishing the level of the levy creates challenges. The House of Lords report sets out are options to achieve this94.

To understand the total amount required we can draw on evidence from other jurisdictions and delineate the range of NHS and third sector services that are required (see Appendix 2) – making comparisons with the costs of other comparable treatment services in Great Britain. Information from the forthcoming evidence review by PHE will also inform this needs assessment95,96.

To date, a broad-based figure of one percent of GGY is the one that has been most widely proposed for the GB context. This approach would avoid the delays and complexities that would be inherent in a so called ‘smart levy’ – where the formula for calculation would be a matter of dispute between sectors and operators. Moreover, unlike the sugar ‘smart levy’, where the tax has the effect of encouraging producers to find ways to reduce sugar content, it is hard to see how a smart levy on gambling could incentivise operators to offer less risky products. The evidence from longitudinal studies does not support the suggestion that there are clear differences in problem gambling rates across different products which could provide an evidence base for formulating a levy. One study found that frequency of purchase of scratchcards was a strong predictor of subsequent problem gambling across time periods. In effect, these types of play can act as part of a pathway to more harmful gambling activities97. A levy on a fixed proportion of GGY avoids these difficulties and creates a clearer and fairer approach to determining how much each operator should contribute.

At current rates a one percent GGY levy would provide £144 million per year98. Whilst this may be the most widely proposed figure, we note the following points of caution:

- It is vital that industry do not view a contribution of this level as discharging their full duty with respect to preventing and treating gambling harms99;

- Experience of other levies shows that once a level is set, they tend to persist. We therefore recommend that the system allows the levy level to flex in response to new evidence and be formally reviewed after two years. This review should take into account factors such as findings of evaluations on what works and research on needs across geographical areas and demographic population groups.

- Business to business companies who provide gambling products do not generate Gross Gambling Yield but do derive profits from their products. A statutory levy would need to be able to obtain contributions from these companies.

Despite the challenges, a one per cent of GGY levy would create the step change in funding that is needed. Great Britain lags behind other jurisdictions in terms of its investment in reducing gambling harms. Countries with well-established government infrastructures and sustainable funding via public health bodies and research councils have a significantly higher ratio of spend per high risk (problem) gambler100. Table 2 shows the relative spend per person, in three comparable jurisdictions101.

Table 2: Research, Education and Treatment spend in four jurisdictions (2018)102

| Jurisdiction | RET Spend per problem gambler | RET spend (£M) | Estimated number of problem gamblers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Britain | 19 | 8.26 | 430,000 |

| Australia103 (3 states) | 368 | 36.58 | 92,138 |

| Canada104 (8 states) | 329 | 43.94 | 145,847 |

| New Zealand | 413 | 9.70 | 235,000 |

The percentage set in other jurisdictions varies. For example, in Ontario, Canada, two percent of gross revenue is allocated by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to fund research and treatment. In New South Wales Australia the levy is also currently set at two percent of gaming revenue, whereas in Victoria the rate is currently 0.68 percent. In New Zealand, the Gambling Act contains a formula for calculating a levy for each sector, using player expenditure and numbers presenting for treatment as part of the calculation, for example the rate for casinos is 0.56 percent and non-casino gaming machines 0.78 percent105.

As noted earlier, evidence from other jurisdictions has suggested that the harms from gambling are of similar magnitude to those of alcohol dependence. Gambling disorder is now classified within the World Health Organisation International Classification of Diseases as a behavioural addiction. It can co-occur with other addictions. However, monetary resources for gambling treatment compare poorly to resources made available for alcohol treatment, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Treatment spend on addictions in England 2016/17

Figure 2 shows that only £15 per person is spent on treatment for gambling disorder, compared with £370 for those with alcohol dependence and £380 for those with drug dependence. If gambling treatment was to be given similar fiscal parity to these two public health issues, the spend on treatment alone would total £1.25 billion, compared to the current spend of £5.5 million. Moreover, this only focuses on one aspect of spend: treatment.

The UK government is also committed to funding prevention for alcohol and drug misuse, noting that interventions result in a social return on investment of £4 for every £1 spent on drug treatment, and £3 for every £1 spent on alcohol treatment (over ten years)106. Whilst the evidence base for what works in gambling harms prevention is in its infancy, a focus on prevention is of primary importance. Drawing on the examples of alcohol and drug dependence strategies, prevention should be considered a priority for significant investment to help develop this evidence base. Research that develops understanding of the inequality in participation and harm is a crucial part of this. Equally challenging are estimates for funding required for research. As noted in Table 1 above, NIHR and RCUK-funded studies for alcohol outnumber those for gambling by a ratio of 31 to 1. To gain equity with alcohol research also requires significant investment.

Ensuring an independent governance infrastructure:

Under current legislative requirements, the proceeds from a statutory levy would be managed by the Gambling Commission. The Gambling Commission would therefore need to establish an infrastructure for distributing these funds. We recommend these should be overseen by a new independent Safer Gambling Levy Board, which could share features with the National Lottery Distribution Fund, the National Lottery Community Fund107 and the Horserace Betting Levy Board108,109.

The requirements of the Board should be that members are free from associations with industry, either perceived or actual, and should not be recipients or potential recipients of the levy monies. The Safer Gambling Levy Board should include at least one member who is an expert by experience110. They should hold expertise in areas needed to support the effective distribution of funds in line with the Commission’s National Strategy for prevention of gambling harms.

The Safer Gambling Levy Board could also play an oversight role in the governance and co-ordination of Regulatory Settlements, one of the Gambling Commission’s enforcement tools for addressing operator’s regulatory failings.

The Safer Gambling Levy Board should use public body infrastructures to support the dispersal of funds. In the case of treatment and prevention this would include the NHS’s GB wide primary and secondary care services, public health and education and third sector provision. In the case of research, this should include dispersal through research councils, drawing on expertise applied in other sectors. However, the Safer Gambling Levy Board would also need the capacity to critically assess gaps in research and any challenges of using existing infrastructure and propose independent ways to address these gaps. For example, funding through independent research councils lends itself to larger, longer-term projects. A smaller funding track (or rapid response research fund) for enabling this kind of work to occur may be needed, especially if gambling research and insight is to keep pace with rapid change and technological developments within the industry.

The approach described above is used to address other major public health issues in the UK. For example, the NIHR PHR Programme has a rapid funding stream which facilitates a rapid response process. There is a general acceptance across all specialities funded through NIHR that digital related research requires a rapid process to keep up with changing forums and behaviours - this is linked to the new NIHR approach of making research more real-world and systems wide so that is relevant to local and national policymakers. Oversight and distribution for this smaller funding track could either be distributed to a funding council or be provided by the DHSC for England and the Government Health Departments in Scotland and Wales. Finally, the Safer Gambling Levy Board would hold a public register of all gambling related research, with a record of outputs, where applicable.

Ensuring that levy funding is only used for gambling-related harms

Some have argued that funding which is generated out of general taxation rather than a levy would be preferable111,112. In New Zealand, this issue has been addressed through a “tax and recover” model, whereby funding for research, prevention and treatment is directed through the Ministry of Health through funds from general taxation but costs are recovered by Treasury from a levy on industry. This provides a further level of separation between industry contributions and spending.

Under current legislative requirements in Great Britain, statutory levy funds would be paid to the Gambling Commission. However, the principle of structural de-coupling could be introduced in other ways. For example, with regards to research, funding could be directed through independent infrastructure, such as the existing research councils.

Our assessment is that in the context of competing priorities for resources, it is unlikely that gambling would ever be allocated the full resources from general taxation needed to effectively reduce harms. Hypothecated duties and levies are increasingly used for ring-fencing public expenditure in the UK as well as elsewhere. Notable examples include:

- Sugar Tax - where all monies go to school sports and other activities to improve health113.

- Vehicle Excise Duty – which, from 2020, is used to fund the majority of Highways England budget114,115.

- Apprenticeship Levy – where companies pay 0.5 percent of turnover for apprenticeship training.

- Illegal Money Lending Levy – paid by banks and other financial institutions to fund action against illegal lending116,117.

- Community Infrastructure Levy – where developers pay a proportion of funds to local authorities that is allocated to community infrastructure projects.

Making it a continuing regulatory requirement to enforce safer gambling:

One challenge of implementing a statutory levy is ensuring that industry do not view this as discharging their full responsibility in terms of safeguarding and protection from gambling harms. Some operators have invested in internal processes and procedures to enhance their ability to reduce harm but there is a need to ensure that all parts of the industry engage with this.

The Commission would continue to make it a requirement of licencing that operators invest in safer gambling practices, and carry out internal audits to ensure compliance with safer gambling standards are met. The levy would not replace the investment required to sustain this. A statutory levy should be the external-facing element of industry responsibilities whilst maintaining a commitment to their internal responsibilities to promote safer gambling amongst their customers and to take action to reduce risk. Any introduction of a statutory levy will require careful framing and communication to ensure both external and internal responsibilities are maintained.

94 (Page 142) Gambling Harm - Time for Action (opens in new tab) , House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry July 2020

95 Gambling-related harms evidence review: scope (opens in new tab), Public Health England, October 2019

96 Harms associated with gambling: abbreviated systematic review protocol (opens in new tab), Benyon et al, Systematic Reviews, June 2020

97 Quinte longitudinal study of gambling and problem gambling (opens in new tab), Williams et al, 2015

98 The GGR of the GB gambling sector has shown a sharp increase over the current decade but much of this was because of the change to point of consumption licensing, which gave a once-and-for-all boost of perhaps £2m per annum. Since then the growth has failed to keep pace with inflation and GGR has fallen a little even in nominal terms in the past year. The initial real level of resources generated by the levy will therefore vary over time.

99 We remain to be convinced that the current voluntary system has a demonstrable positive effect on the Gambling Industry’s commitment to other safer gambling activities.

100 Evidence Exchange Brief - Systems of funding for gambling research (opens in new tab), GREO, January 2020

101 (Page 7) Reviewing the research, education and treatment (RET) arrangements (opens in new tab), Gambling Commission, February 2018

102 Based on statistics from: (Page 7) Reviewing the research, education and treatment (RET) arrangements (opens in new tab), Gambling Commission, February 2018. NB – A number of caveats apply to the figures quoted in Table 2 – as set out in the Gambling Commission’s review document. For example, they do not capture money donated in GB to recipients other than GambleAware. Nor do they capture expenditure in health systems in each jurisdiction to support people with co-morbid conditions. The figures are intended for illustrative purposes only.

103 Figures represent combined states

104 Figures represent combined states

105 Evidence Exchange Brief - Systems of funding for gambling research (opens in new tab), GREO, January 2020

106 Alcohol and drug prevention, treatment and recovery: why invest? (opens in new tab), Public Health England, February 2018

107 The National Lottery Distribution Fund (NLDF) was set up when the National Lottery was formed in 1994 to receive and hold monies generated by the National Lottery for good causes. Funds held in the NLDF are apportioned to the arts, sport, national heritage and community causes based on a set percentage detailed in the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 (opens in new tab). Each distributing body run a series of grant programmes to distribute the funds to beneficiaries/good causes. The National Lottery Community Fund, which receives 40% of the funds, is one example of a distributing body. The National Lottery Community Fund is a non-departmental government body which is governed by a Board comprising the Chair (who is the Chair of the UK committee), the chairs of each of the four country committees and up to seven other members. The Board sets the Fund’s Strategic Framework, and each committee working within this framework has delegated authority to determine the programmes delivered within their country. They also make grant decisions, or agree the delegated arrangements for making them, within their programmes.

108 Horserace Betting Levy Board (opens in new tab) - website

109 (Page 142) Gambling Harm - Time for Action (opens in new tab), House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry July 2020

110 The Levy Board should also link in to structures being developed in Scotland, Wales and England to involve a wider network of experts by experience in the implementation of the National Strategy for Reducing Gambling Harms.

111 Gambling Research and Industry Funding (opens in new tab), Collins et al, Journal of Gambling Studies, 2019

112 Funding of gambling studies and its impact on research (opens in new tab), Nikkenden et al, Nordic Studies on Drugs and Alcohol, 2019

113 Soft drinks levy comes into effect (opens in new tab), HM Treasury, April 2018

114 Roads funding: information pack (opens in new tab), Department for Transport, 2018

115 Vehicle excise duty (opens in new tab), House of Common Library, November 2017

116 Stop loan sharks (opens in new tab) - website

117 Illegal money lending levy (chapter 13) (opens in new tab), FCA handbook, FCA, November 2019

Section 6: Transitional arrangements

It is acknowledged that there are weaknesses in the current system of distributing funding for research, treatment and prevention118,119,120. Despite recent efforts by the Gambling Commission and others to strengthen the voluntary system, there continues to be a lack of independence, transparency, equity, and sustainability of funds.

The House of Lords Report highlighted the government’s powers under Section 123 of the Gambling Act to create a mandatory levy121. There are a number of transitional arrangements that could be put in place to address some of the current challenges with funding for existing services. For example;

All existing funds for research from voluntary contributions could be re-distributed to the UK’s mainstream funding Councils such as ESRC, NIHR and RCUK with a much faster time frame for commissioning research, as well as other third sector organisations. This would include the funding ring fenced for the independent data repository. GambleAware could phase out all funding of research, without disadvantaging existing researchers or projects currently in receipt of funds, and transfer all remaining funds to the new Levy Board. Existing funded projects would be maintained for the duration of their contracts.

The Commission could establish a time limited ‘shadow’ Board as a precursor to the Safer Gambling Levy Board to distribute funding and administer regulatory settlements. Board appointments would include those with experience of distributing public funds and reflect the principles of transparency and accountability122. At least one member of the Board would be an expert by experience123. Operators would no longer pay regulatory settlements directly to researchers, but the monies would be submitted to the Levy Board for decisions about distribution. This would, in effect, create involuntary research funding or structural de-coupling of the type established elsewhere124.

118 Clear principles are needed for integrity in gambling research (opens in new tab), Livingstone & Adams, Addiction, 2015

119 Public Health England’s capture by the alcohol industry (opens in new tab), Bauld, BMJ, 2018

120 Online Gambling Harm Inquiry – Interim Report, Report from the Gambling Related Harm All-Party Parliamentary Group, November 2019. This link was available at the time of publishing but is no longer available.

121 This would be achieved by implementing Section 123 of the Gambling Act 2005 (opens in new tab)

122 Seven principles of public life (opens in new tab), UK Government

123 The Levy Board should also link in to structures being developed in Scotland, Wales and England to involve a wider network of experts by experience in the implementation of the National Strategy for Reducing Gambling Harms.

124 Evidence Exchange Brief - Systems of funding for gambling research (opens in new tab), GREO, January 2020

Section 7: Conclusions

This advice has reviewed the evidence regarding the introduction of a statutory levy to fund research, prevention and treatment of gambling harms across Great Britain. Such a levy would bring benefits for the public, for government and for the industry.

- For the public, it would allow predictable sustainable and fully integrated service provision, early identification and better coordination with established third sector organisations that currently struggle to provide the levels of service that are needed.

- It would bring benefits to government and society as investment would deliver economic returns in reducing the social costs of gambling harms and drive a culture of independent research and innovation.

- It would create equity for the industry, as all gambling operators would contribute to investing in addressing harms. This would have the potential to help address declining public trust in the industry.

Advisory Board for Safer Gambling – Our role125

The Advisory Board for Safer Gambling provide independent expert advice with the aim of achieving a Great Britain free from the consequences of gambling-related harms. Our role is to:

- Help deliver the National Strategy to Reduce Gambling Harms

- Help increase research capacity and capability through engaging with a wide range of experts

- Help share findings about best practice so they have an impact

- Help solve policy dilemmas where research evidence is lacking or ambiguous.

125 Advisory Board for Safer Gambling - website

Appendix 1: Summary of psychological treatment approaches

Summary of psychological treatment approaches

This Appendix provides a summary of the current psychological therapies, which typically address psychological (cognitions, cognitive dissonance), emotional (emotional dysregulation), behavioural (impulse control) and contextual (e.g. environmental cues) factors that are associated with gambling in a problematic pattern. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) currently has the strongest evidence base as an intervention, but other forms of intervention have also demonstrated effective outcomes.

Cowlishaw et al126, Rizeanu127, Menchon et al186 and Sancho et al129 have conducted problem and pathological gambling treatment reviews and have identified, based on the strength of the evidence, four types of psychological treatments:

1.1 Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (commonly referred to as CBT)

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy currently has a strong evidence base, which may be due to the availability of randomised clinical trials. CBT consists of a collaboration between client and therapist that seeks to engage the client in Cognitive Restructuring (re-evaluating erroneous beliefs e.g. about gambling randomness, ability to identify systems of winning or recoup losses), increase awareness of biases in information processing and thinking style, teach problem-solving training and social skills training. Relapse Prevention involves increasing awareness of the cues or triggers for relapse and identifying alternative adaptive coping strategies. Based on the available evidence Cognitive Behaviour Therapy is considered best practice at this time.

1.2 Motivational Interviewing Therapy

Motivational Interviewing Therapy currently has some evidence of effectiveness, although the available evidence is for less severe gambling problems. Motivational Interviewing is a client-centred counselling style that seeks, in a non-judgemental conversation, to increase awareness of the costs and benefits of a behaviour. It also seeks to create cognitive dissonance by shifting the motivational balance away from ambivalence toward eliciting change talk in the form of self-motivational statements and increasing the client’s perceived importance and confidence in the possibility of change. Motivational interviewing also includes motivational enhancement therapy.

1.3 Mindfulness-based interventions

Mindfulness-based interventions currently have some evidence of effectiveness. As applied to gambling problems, mindfulness-based interventions are based on the premise that emotional dysregulation and impulse control difficulties underpin pathological gambling. Mindfulness-based interventions comprise of a treatment that aims to promote increased mindful awareness of thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations, acceptance, paying attention in the moment to thoughts and feelings without judgement. A combination of psycho-education, mindfulness-based interventions plus CBT maybe able to improve to improve secondary emotional dysregulation in addition to the benefits of traditional Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.

1.4 Other Psychological Therapies

Other Psychological Therapies include Psychodynamic therapy, Aversion Therapy, 12-step (Gamblers Anonymous, GA), Integrative therapy and self-exclusion. They have weak or no evidence, this may be due to the lack of research trials. GA has been used as the control condition in some research trials.

2.0 Treatment Effectiveness

2.1 National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) Recommendations

Currently there are no NICE guidelines available recommending the best treatment approach and models of service delivery, however, this Quality Standard (GID-QS10099) has been referred to NICE (July 2018) but has not been scheduled into the programme of work. Expected publication date to be confirmed.

2.2. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, Motivational Interviewing, Twelve Step facilitated group therapy

The latest Cochrane review was published 14th November 2012. It reviewed psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling. It systematically reviewed the literature and identified 14 randomised controlled research trials of psychological therapies for pathological and problem gamblers130. The review assessed the research trials for the efficacy and durability of treatment effects. The psychological therapies included Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) (11 research trials), Motivational Interviewing therapy (4 research trials), Integrative therapy (2 research trials) and Twelve Step facilitated group therapy (1 research trial). The interventions were delivered by highly trained Clinicians under supervision (e.g. Clinical Psychologists, Cognitive Therapists, Masters level Counsellors, Clinical professionals).

The control condition was no treatment controls or referral to Gamblers Anonymous. The primary outcomes they used to assess how effective treatment were: Gambling symptom severity, financial loss and gambling frequency. The secondary outcomes they used to assess how effective treatment was were symptoms of depression and anxiety. Assessment of outcomes was at 0-3 months post-treatment.

The review identified that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) (11 research trials) compared to control groups significantly experienced beneficial effects from treatment in terms of reduced Financial Loss (medium effect size) and Reduced Gambling Symptom Severity (very large effect size). It found that Motivational Interviewing therapy (4 research trials) led to significantly reduced Financial Loss from gambling, however the participants in those research trials had less severe gambling problems. There were no significant effects of therapy for Integrative therapy (2 research trials). For Twelve Step facilitated group therapy (1 research trial) some beneficial effects were identified. The review concludes there is evidence supporting Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), Motivational Interviewing therapy and Twelve Step facilitated group therapy. The review supports the efficacy of CBT in reducing gambling behaviour and other symptoms of pathological and problem gambling. However, the review was unable to assess the longer-term durability of treatment effects. The finding that CBT is effective in the treatment of problem gamblers has been supported by later reviews and studies.

Abbot et. al.131 has published a research protocol to conduct a pragmatic randomised control trial that will seek to address the shortfalls of previous research trials. They will compare a motivational intervention to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy and randomly allocate participants in a community treatment agency in New Zealand to one of the treatments. The motivational intervention will consist of one session of face-to face motivational interviewing and a self-instruction booklet plus five follow-up telephone booster sessions. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapy will consist of ten face-to face sessions. They will assess outcomes over a longer time period up to 12 months. The primary outcomes will be days spent gambling and money spent gambling per day in month prior. The secondary outcomes will be problem gambling severity, urges, cognitions, mood, alcohol and drug use, psychological distress, quality of life and costs.

2.3 Mindfulness-based interventions

Sancho et al. (2018)132 conducted a systematic review of Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of a range of substance and behavioural addictions that included gambling as a behavioural addiction. The review sought to assess the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of these addictions. They reviewed 54 randomised control trials between 2009-2017. The mindfulness-based interventions included some mindfulness-based relapse prevention and were typically weekly for between 1-3 hours, delivered in a group format by two therapists, for a total of between 7-12 sessions. The review found that for pathological gambling Mindfulness-based interventions were effective.

126 Psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling (opens in new tab), Cowlishaw et al, Cochrane Library, 2012

127 Pathological gambling treatment – review (opens in new tab), Rizeanu, Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2015

128 An overview of gambling disorder: from treatment approaches to risk factors (opens in new tab), Menchon et. Al, F1000 Research, 2018

129 Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of substance and behavioural addictions (opens in new tab), Sancho,. et. al. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2018

130 Psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling (opens in new tab), Cowlishaw et al, Cochrane Library, 2012

131 Effectiveness of problem gambling interventions in a service setting: a protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial (opens in new tab), Abbott. et al, BMJ Open, 2017

132 Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of substance and behavioural addictions (opens in new tab), Sancho. et. al. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2018

Appendix 2: Areas of treatment, education and research related to gambling harms covered by a statutory levy

Third sector services

Deliverables:

- National Helpline

- On line support services (computerised CBT)

- Peer and family support services

- People with lived experience involved in co-design, evaluation

- Community Based Treatment

- Residential centres

- Money management and debt advisory services

- Outreach work in prisons.

NHS Services

Primary Care and other front-line health care staff (e.g. AE, Mental health, antenatal)

Deliverables:

- Integrated primary care led services for early identification first contact care, signposting, provision of psychological education, physical health care and prescribing, with involvement of those with lived experience.

Intermediate-integrated team (IMIT) This would be made up of generalist-led (ideally GPs) with community providers

Deliverables:

- Assessment and formulation

- Treatment (pharmacological as well as talking therapies)

- Case management.

Specialist

Deliverables:

- Liaison with GPs and other community providers as necessary

- Providing services for those with complex needs and serious co-morbidities, or those who require specialist interventions such as naltrexone or specialist forms of talking therapies will be referred to secondary care services.

- Focus on prevention, research, service development as well as complex patients

- Specialist centres in England (13), Scotland (3) and Wales (2)

- Day and Inpatient services.

Quality Assurance of NHS funded services

Deliverables:

- CQC, Health Improvement Scotland Healthcare Inspectorate Wales

Public health services

Deliverables:

- Supporting universal and targeted education and prevention work in schools, universities, places of work and leisure facilities.

Social marketing campaigns

Deliverables:

- Targeted campaigns such as suicide prevention working with industry and financial sector partners.

Research collaboratives/centres

Deliverables:

- Large scale randomised controlled trials and prevalence studies

- Behavioural research (characteristics of those harmed by gambling activities)

- Technical innovations (social enterprise software).

Data repository

Deliverables:

- Creation and maintenance of a national data repository with data requirements mandated by the Commission, subject to robust governance and oversight.

NIHR and RCUK funds

Deliverables:

- Funding for longitudinal studies with different populations (BAME, young men, women, disadvantaged groups), epidemiological studies, public health studies, game design and patterns of play impact of advertising, use of avatars social media research using machine learning, loot boxes and their relationship with gambling, gaming and its relationship with gambling, esports, research with young children on their emerging relationship with gambling.

Safer Gambling Levy Board

Deliverables:

- Oversight of distribution of funds

- Rapid response research funds.

Appendix 3: Research Council funded studies in comparable areas with costs

Case study 1: Medical Research Council

Alcohol Harms: The relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular risk - A life-course perspective

Award: £316,235

Start Date: January 2015

End Date: June 2018

Research type: Primary Research

Health Category(s): Cancer, Cardiovascular, Respiratory, Stroke

Contracting Organisation: University College London

Research Call: Research Grant

Summary:

The relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is complex and controversial. Meta-analyses suggest that those who consume alcohol in moderation have a lower risk of developing CVD than heavy drinkers and those who abstain. However, the majority of studies measure alcohol at only one point in time and therefore fail to take into account variation in drinking over time. This approach means that important transitions, such as from heavy drinking to abstinence or low-drinking are not captured.

This particular change has been put forward as a potential explanation for the apparent U/J-shaped relationship between alcohol and CVD, as it may be that that those classified as non-drinkers are actually former heavy drinkers who quit due to ill-health (referred to as "sick-quitters"). Jointly examining the relationship between longitudinal typologies of drinking and CVD improves understanding of the association between changes in alcohol consumption over time with respect to developing CVD. In doing so, our findings can be used to develop dynamic predictive tools accounting for repeat measures of alcohol consumption across the life-course and thus provide individualised/age-specific drinking guidelines.

We proposed using our existing infrastructure of 9 UK cohorts (sample size 59,397 with 163,710 alcohol observations) with harmonised alcohol measures, and with linkages to external outcome databases (mortality, GP, hospital records), to explicitly examine the role of alcohol consumption in the development of CVD using a life-course perspective.

Results: 10 publications https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=MR%2FM006638%2F1 (opens in new tab)

NIHR Policy Research Programme

Recovery pathways and societal responses in the UK, Netherlands and Belgium- REC-PATH

Award: £246,886.00

Start Date: July 2017

End Date: December 2020

Research type: Primary Research

Health Category(s): Mental health

Contracting Organisation: University of Sheffield

Research Call: Research Grant

Summary:

Recovery models are well established in policy, commissioning and treatment practice in the UK, but have only begun to emerge in policy discourse in the Netherlands and Belgium. The aim of this project is to map pathways to recovery in populations engaging with different mechanisms of behaviour change for recovery - mutual aid (such as 12-step groups like NA), peer-based support, residential and community treatment, specialist treatment: maintenance and abstinence oriented) or through their own 'natural recovery' endeavours, at different stages of their addiction careers.