- Print the full document

- Save the page as a HTML document to your device

- Save the page as a PDF file

- Bookmark it - it will always be the latest version of this document

This box is not visible in the printed version.

Evidence gaps and priorities 2023 to 2026

The themes we are focusing on over the next three years to improve the evidence base for gambling in Great Britain.

Published: 23 May 2023

Last updated: 27 May 2025

This version was printed or saved on: 16 February 2026

Online version: https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/about-us/guide/evidence-gaps-and-priorities-2023-to-2026

Overview: Evidence matters. We all make decisions based on how we understand the world around us, what the evidence is telling us. The bigger the decision and the wider it’s impact, the more likely we all are to want more information before we act. Before the big choices, we all want to fill in the gaps in our understanding.

What’s true for us all in our daily lives is just as true for our understanding of gambling.

At the Gambling Commission we are a people focussed and evidence-led regulator. That means we recognise that better data, better research and better evidence will lead to better gambling regulation and better outcomes for consumers who gamble, their communities and the gambling sector itself.

And that’s what makes identifying evidence gaps and priorities for further data and research so important. In the following chapters, you will read about the themes and issues that require the development of further evidence and focus over the next three years if we are to usefully and significantly improve the evidence base for gambling in Great Britain. As you would expect, they all relate to our role as regulator to keep gambling safe, fair and crime free. It builds on the discussions and feedback we received at our very successful conference - Setting the Evidence Agenda - and also draws on what we have learned as we developed our gambling typologies and Path to Play research.

However, I think it’s important also to be clear that this document is not only about the Commission and what we need to do. Similarly, it does not argue that you should only act when the evidence base is completely conclusive. This paper is about highlighting the challenges ahead and asking the questions that need answering. Answering those questions is something we can all play a part in.

We have identified six themes that, whilst we already have evidence and data, we think are a priority to make a concerted effort to strengthen the evidence base. They are:

- early gambling experiences and gateway products

- the range and variability of gambling experiences

- gambling-related harms and vulnerability

- the impact of operator practices

- product characteristics and risk

- illegal gambling and crime.

Each area has key points where we want to know more, each area has clear actions that the Commission can lead on but equally, they each have work for others: researchers, third sector bodies and the gambling sector itself.

We are building on a strong foundation, but with the Gambling Act Review White Paper now published, it’s clear that the next few years give a real opportunity to make decisive progress towards gambling in Great Britain being safer, fairer and crime-free. If we can all play our part in addressing the evidence gaps identified, I know we will have the tools to make the most of that opportunity.

Tim Miller, Executive Director of Research and Policy

Glossary of terms used in our evidence gaps and priorities

- Affected others

- Somebody harmed by the gambling of another person. This can include the gambler’s partner, their children, their wider family and friends and other social contacts.

- Children

- Consistent with the Gambling Act 2005 (opens in new tab), a 'child' is an individual less than 16 years old, and a 'young person' is an individual who is not a child but is less than 18 years old.

- Data

- When we refer to data, we mean digital information about people, companies and systems. While the legal definition of data covers paper and digital records, the focus of this document is on digital information. Depending on context, this could be administrative, operational and transactional data as well as analytical and statistical data.

- Early gambling experience

- These could occur at any age and on any gambling activity, including the gambling – and gambling-adjacent – activities that are legal for children under British legislation. They are most likely to be experienced in childhood, as a young person or a young adult, but that is not always the case.

- Gambling experiences

- Any experience with a gambling activity, whether it is regulated - such as gambling with licensed operators for betting, casino, bingo, arcade or lottery products - or unregulated gambling such as private betting or poker games with friends.

- Gambling harm

- Gambling-related harms are the adverse impacts from gambling on the health and wellbeing of individuals, families, communities and society.

These harms are diverse, affecting resources, relationships and health, and may reflect an interplay between individual, family and community processes. The harmful effects from gambling may be short-lived but can persist, having longer-term and enduring consequences that can exacerbate existing inequalities. - Gateway products

- This refers to the product on which an individual initially gambles or gambling-adjacent activity that makes it more likely that they gamble in the future. Gateway products are likely to be different for different people, and can be encountered at a variety of ages.

- Operator practices

- This term covers any actions by operators that impact upon consumers, including decisions related to gambling environments and communications with consumers.

- Problem gambling

- Gambling to a degree that compromises, disrupts or damages family, personal or recreational pursuits. We currently measure problem gambling prevalence rates via a number of screening tools including the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI).

- Vulnerability

-

A customer in a vulnerable situation who, due to their personal circumstances, is especially susceptible to harm, particularly when a firm is not acting with appropriate levels of actions they should take as a result.

Although not an exhaustive list, we do for regulatory purposes consider that this group will include people who spend more money and/or time gambling than they want to, people who gamble beyond their means, and people who may not be able to make informed or balanced decisions about gambling (for example because of health problems, learning disability, or substance misuse relating to alcohol or drugs). - Young adult

- Individuals aged between 18 and 24 years old.

Background to our evidence gaps and priorities

The Gambling Commission uses a range of data, research and insights to inform the decisions that we make and provide advice to the Government about gambling behaviour and the gambling market. We are responsible for the production of official statistics on the size and shape of the gambling industry, rates of participation in gambling, and the prevalence of problem gambling, in both adults and children. In addition, we track wider trends in consumer behaviour, listen to the full breadth of consumer voices, and deep dive quantitatively and qualitatively on key issues, impacts and emerging areas of interest.

We are a people focussed and evidence-led regulator. To be the most effective regulator possible, however, we require a robust evidence base - and the current evidence base still has many gaps. A lack of conclusive evidence does not necessarily mean that action shouldn’t be taken (for example, we sometimes apply the precautionary principle where we are satisfied that there is sufficient risk of harm), but we should aim to have as much reliable evidence as possible on which to base our decision.

Here, we present our ambitions and vision for developing the evidence base over the next three years and outline the gaps that we believe can and should be filled. We have gone through an extensive process to identify these gaps and priorities for improving the evidence base, all of which relate to our regulatory duty under the Gambling Act 2005 (opens in new tab) to:

- prevent gambling from being a source of crime or disorder, being associated with crime or disorder, or being used to support crime

- ensure that gambling is conducted in a fair and open way

- protect children and other vulnerable people from being harmed or exploited by gambling.

And under the National Lottery etc Act 1993 (opens in new tab) to:

- ensure that the interests of all players are protected

- ensure the Lottery is run with due propriety

and subject to those two requirements:

- that returns to good causes are maximised.

This forward look demonstrates where we intend to focus our efforts in the next three years, within the parameters of our existing resources and remit, in line with the contents of DCMS’s White Paper following the review of the Gambling Act. It also identifies where we feel there is a wider evidence need, but where the Commission is not the right organisation to lead on delivery.

We have identified six overarching themes which cover the full range of gaps and research questions that we need to be able to fill and answer within our regulatory scope. Whilst we have a set a direction of travel, we will continually revisit and refresh these priorities as we react to progress and emerging findings from across the gambling research ecosystem.

Our approach to evidence-based regulation and evidence assurance

The approach that we have taken to identify evidence gaps and priorities is underpinned by the principles of Evidence Assurance. Evidence Assurance is a process we use that ensures that decisions we make are underpinned by the best available data and evidence and is based on recognised principles.

We use a rigorous, consistent, and transparent process to collate, interpret and weigh up the overall strength of the evidence base for a given issue or topic. Where there are gaps in the evidence base, we are transparent about that and identify what ideal evidence would look like, and how those gaps could be filled.

Our evidence assurance process is underpinned by a five-phase approach:

- What is the question, issue or problem?

- What would the ideal evidence base look like?

- What do we have in reality, and what are the evidence gaps?

- What is our assessment (quality and quantity) and interpretation of the evidence base?

- How does this inform our advice, position and or next steps?

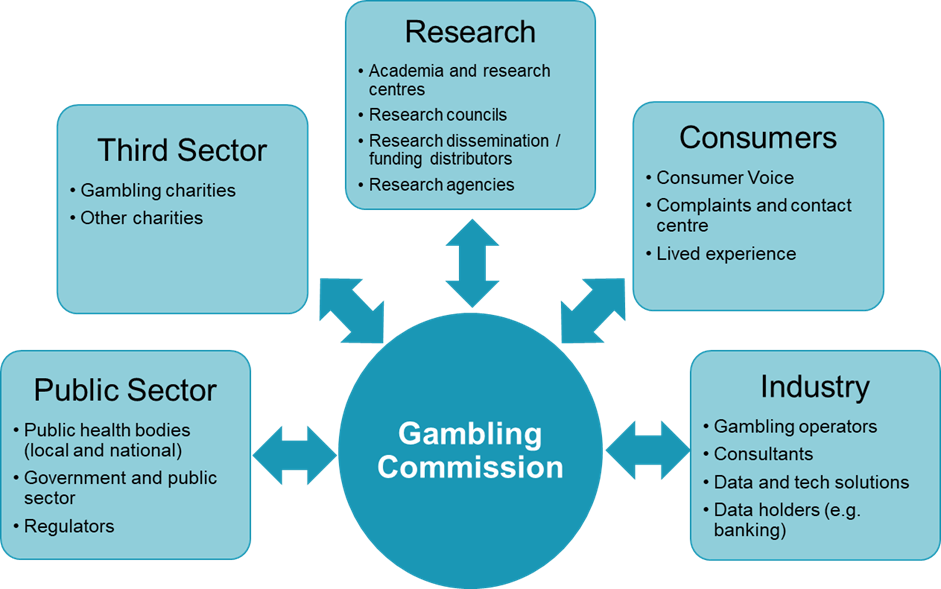

Our role in the evidence ecosystem

We work with a variety of stakeholders and interested parties to gain insight and perspective about gambling behaviour in Great Britain. This helps to support our own commissioned research, statistics, regulatory casework and operator data analysis, to build a large volume and diverse range of evidence. We also have ready access to the widest range of experience and perspectives through our expert panels.1

Our forward plans also include developing our capacity to be a proactive, data led regulator, using the power of data and advanced analytics to make us more efficient and effective in carrying out our regulation.

The Commission contributes to the wider ecosystem by:

- collecting and publishing official statistics

- conducting wider research and data analysis

- providing and publishing evidence-based advice to government and other stakeholders

- using our data and research from the wider ecosystem to monitor changes that may have an impact on the regulatory framework.

There are five key groups of stakeholders that make up the wider evidence ecosystem:

- public sector – including local and national government, wider public sector, public health bodies (both local and national), and other regulators (national and international)

- third sector – including gambling charities and other charities

- research - including academia and research centres, research councils, research dissemination organisations and funding distributors, and research agencies

- consumers – via our consumer research, complaints and contact centre engagement, as well as engagement with people with lived experience of gambling harms and affected others

- industry – including gambling and lottery operators, consultants, data and technology solutions companies, and other data holders (for example banking).

Notes

1 The Advisory Board for Safer Gambling (ABSG), Digital Advisory Panel (DAP) and Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP).

The gambling landscape – what we already know

According to recent figures, approximately 25.8 million people aged 16 and over gamble on products in Great Britain every four weeks, with approximately 14.5 million doing so on products licensed under the Gambling Act 2005.2

It is important not to always consider the gambling sector as a uniform sector – from an industry or consumer perspective.

The gambling sector we regulate comprises a diverse range of products used by a wide range of consumers. Consumers play on different products, for different experiences, and in different environments (in-person or online) which offer differing levels of anonymity and availability. Our research into why people gamble shows it can be an opportunity to socialise or a moment of ‘me time’. It can be a niche activity, or something engaged in by the mainstream.

It is also impacted by the context around it. Sometimes this is by highly visible products that are classed as gambling, like the National Lottery. Sometimes, it could be products that have gambling-like mechanics, such as loot-boxes. It could even be the macro trends that impact everything around us, such as the Covid-19 pandemic or the ongoing pressure on the cost of living. This can make it a complex landscape to unpick or generalise.

The biggest change in the gambling landscape over recent years is a shift to online play, reflecting our lifestyles in general. Technology and globalisation have meant that gambling is no longer confined to opening hours and largely local events, but instead a 24/7 opportunity and global event-driven marketplace.

With 94 percent of UK adults having access to the internet in 2021 it is not surprising that our industry statistics show a long-term trend of increasing online gambling participation and a decrease in land-based gambling. This matches changes seen in other sectors such as the increase in online grocery shopping or the rising popularity of digital-only banks.

Whilst the popularity of gambling in person has declined over time, retail remains a significant part of the sector.

Against this backdrop of changing trends, our data shows that although the vast majority do not experience gambling-related harms, there are still significant numbers of people who do encounter issues with their gambling.

The precise measurement of gambling behaviour and harms is complex, and needs continual development, however, we do know that hundreds of thousands of gamblers are suffering negative consequences from their gambling.

Within those numbers we know that some people are more likely to experience harm than others, including those who engage in multiple activities, men, those with probable mental health issues and players with the highest gambling expenditure. We also know that those suffering gambling-related harms are not a static group, so understanding the individual better and appreciating what works to help those avoid or recover from harm is a key part of advancing our understanding.

Notes

2Gambling behaviour in 2022: Findings from the quarterly telephone survey, Gambling Commission, 2023: 44.4 percent engaged in all gambling in the past four weeks, with 29.2 percent excluding National Lottery only.

Estimates of the population for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (opens in new tab), Office for National Statistics, 2022: mid-year estimates for June 2021 shows a British population for those aged 16 and over as 53,195,320.

Evidence gaps and priorities 2023 to 2026 - Reflections on Year 1

The first year of our Evidence Gaps and Priorities programme has been a busy one. The Gambling Commission’s focus has been on embedding our key priorities both internally and across the evidence ecosystem. We have also made progress on the delivery of our core evidence vehicles, to build firm foundations for improving the evidence base.

We have completed the development of the new Gambling Survey for Great Britain (GSGB), and have published the first two waves of official statistics on levels of gambling participation. We are now working towards our first annual publication and the release of new data on the impacts of gambling, including the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) and gambling-related harms. A huge amount of work has gone into developing a robust survey that is fit for the future, and we were pleased that our approach was endorsed in an independent assessment conducted earlier this year. While we will continue making improvements in the coming months and years, we will soon have an unprecedented volume and breadth of data on reported consumer gambling behaviour. This will help us to make greater progress on addressing the evidence gaps we’ve identified.

Alongside the GSGB we have also delivered several projects under our Consumer Voice programme. These projects have taken identified gaps in the evidence base and used a range of consumer research approaches to improve our understanding of elements of the consumer journey and gather both quantitative and qualitative evidence to support our work. Several of the projects involved direct engagement with consumers, conducting face to face focus groups to ensure that the voices and experiences of a wide range of consumers are considered in the work that we do. We engaged with nearly 40,000 consumers through our research (including the first two waves of the GSGB) in 2023 – a level that we hope to continue.

This year has also seen the introduction of our Data Innovation Hub, which has been set up to make faster progress in establishing data-led solutions and increasing our capacity and capability to access and analyse large datasets from a range of sources. In the last year we have used data science techniques to explore new data sources, including open banking data and piloting the use of open-source data from X (formerly known as Twitter) and Meta. We are also improving the way that we collect core regulatory data from gambling operators and are moving into the pilot stage of collecting a more detailed daily operator dataset.

We are also beginning to build our knowledge around the size of the unlicensed online gambling market, and the pathways consumers use to access it; however there will be more work done on this topic in the coming months. Whilst we conducted some small longitudinal research projects last year as part of the Consumer Voice programme, we still need large scale longitudinal research conducted over longer time periods to really understand how behaviour changes over time and the factors that influence those changes. The GSGB presents a fantastic opportunity to recontact respondents for further research, so we will be exploring the feasibility of developing longitudinal follow ups in the year ahead. We will also be expanding our use of open-banking data for longitudinal analysis of consumers’ gambling behaviour and spend. We also note the need to build evidence of the impact of changes being made following the implementation of the Government’s white paper, with the Commission and DCMS working together with NatCen to design a framework of potential evaluation approaches.

Going forward, in line with our recently published Corporate Strategy (2024 to 2027), we will continue our efforts to progress our thinking and develop our capacity and capability to improve the data and evidence that we use to regulate. Stakeholder feedback has suggested the need for clear roadmaps to help to show where we are hoping to get to with the six evidence themes outlined in our Evidence Gaps and Priorities. We are also continuing to improve the governance arrangements that sit around the work that we do and intend to develop this further in the year ahead.

We will continue to reach out to stakeholders across the evidence ecosystem to bring their insights and findings into the Commission and will include the broadest range of perspectives in our work. We have been pleased to see stakeholders engaging with our Evidence Gaps and Priorities and aligning their work to the 6 evidence themes. We look forward to seeing the results of the many projects and programmes that are underway. Our most recent evidence conference demonstrated how different parties, with different perspectives and expertise to offer, can come together to discuss the big issues facing the sector and share ideas and reflections. We welcome even more collaboration and innovation going forward and look forward to showcasing more work from across the ecosystem at next year’s conference. This year’s event was titled ‘Better Evidence, Better Outcomes’ and the Commission intends to continue working towards this goal in the year ahead.

Our Evidence Gaps and Priorities were always intended to be a living document. It is therefore important to reflect on the progress that has been made at this one-year point, and so the pages for each evidence theme have now been updated with key milestones and contributions that have been made in the last year. These cover examples of our own research and analysis, but also examples of work from across the evidence ecosystem. Whilst only a small reflection of the amount of work that has been carried out, they are pieces that have been particularly useful in filling known evidence gaps and informing the Commission’s work. We encourage all parties working in this space to continue to share the great work that they are doing with us so that we can continue to regulate gambling on the basis of robust, high-quality evidence.

Our evidence themes and how they link to the Path to Play framework

Evidence theme 1

Early gambling experiences and gateway products

Theme 1 details for early gambling experiences and gateway productsEvidence theme 2

The range and variability of gambling experiences

Theme 2 details for the range and variability of gambling experiencesEvidence theme 3

Gambling-related harms and vulnerability

Theme 3 details for gambling-related harms and vulnerabilityEvidence theme 4

The impact of operator practices

Theme 4 details for the impact of operator practicesEvidence theme 5

Product characteristics and risk

Theme 5 details for product characteristics and riskHow our priorities link to the Path to Play framework

The Path to Play framework identified stages that are present in each gambling journey:

- passive influences

- external triggers

- internal impulses

- active search

- play experience

- play outcome.

Each of the six evidence themes we have identified can be mapped to the Path to Play and shows the need for further research covering the breadth of the customer journey.

There is significant crossover across some of the evidence themes and the stages of the Path to Play, however, we have highlighted the primary areas of overlap as follows:

Early gambling experiences and gateway products

These primarily contribute to the ‘passive influences’ stage of the Path to Play.

The range and variability of gambling experiences

As suggested by the name, the topics of this theme impact every stage of the Path to Play: ‘passive influences’, ‘external triggers and internal impulses’, ‘active search’, ‘play experience’ and ‘play outcome’.

Gambling-related harms and vulnerability

Vulnerability, in particular, is significant for the ‘external triggers and internal impulses’ stage of the Path to Play, with the topics in this theme also affecting the ‘play experience’ and ‘play outcome’ stages.

The impact of operator practices

As detailed in the relevant section, the impact of operator practices stretches from ‘external triggers and internal impulses’, the ‘active search’ stage and impacts the ‘play experience’.

Product characteristics and risk

These factors are most likely to have an impact on the ‘active search’ and ‘play experience’ stages of the Path to Play.

Illegal gambling and crime

Aspects of this theme relate to the ‘external triggers and internal impulses’ and ‘active search’ stages, with the theme also linked to the ‘play outcome’ stage.

Each of the priority themes is explained in more detail in the following sections, along with our rationale for their inclusion as priorities and some indicative, aspirational questions. The Commission is not in a position to deliver a research programme to address all of these questions – some of which are extremely complex – so a brief note outlining steps that we will be prioritising as part of our own research delivery is included for each theme.

Evidence theme 1 - Early gambling experiences and gateway products

Evidence theme 1 - Early gambling experiences and gateway products

This theme is about:

- understanding the gambling behaviours of children (under 16 years old), young people (those aged 16 and 17 years old) and young adults (18 to 24 years old) and what their journeys into gambling look like

- how other consumers, including those with vulnerabilities, are introduced to gambling and how this influences their behaviour

- how consumers engage with new products and activities that are not gambling but have similarities to gambling.

The Commission’s Path to Play research highlighted the impact of ‘passive influences’ on people’s gambling, with underlying attitudes and perceptions of gambling having an overarching impact on consideration and experience of play. These passive influences evolve gradually over time, starting with people’s early gambling experiences.

Young people have increased vulnerability to gambling-related harm due to their evolving biological and neurological development.3 This state of increased risk is recognised through age restrictions that limit access to activities within the regulated gambling market such as betting, attending casinos and playing National Lottery products. However, there are also activities which are assessed as being lower-risk and do not have age restrictions, such as ‘penny-push’ machines in arcades. Our young people and gambling research found that these products (which have been associated with adult gambling4) and activities that cannot be regulated, such as placing bets with friends or family, are often an individual’s first interaction with gambling.

The impact of activities that are gambling-adjacent or blur the line between gambling and gaming – an example of which may be loot box features in computer games, are also relevant factors, especially given fast-paced changes in consumer behaviour.5 There is also an interest in the long-term impact of gambling advertising, our young people and gambling research shows that it is widely seen, and concerns have been raised about a ‘normalising’ effect.6

Within Great Britain, our young people and gambling research with children up to the age of 16 shows that informal gambling participation, such as picking numbers for a lottery ticket and sweepstakes with family or friends for events such as the Grand National is common. We also know that children's participation in regulated gambling activities predominantly occurs with the supervision of a parent or guardian.

Although we know that passive influences can impact somebody’s decision to gamble, it can be difficult to determine the extent of early gambling experiences within those influences compared to more recent gambling experiences of themselves and others, or the impact of advertising, for example. Longitudinal evidence in Britain suggests that gambling activity can increase or decrease significantly in early adulthood (between the ages of 17 and 21) when many individuals experience greater social and financial freedoms.7, 8.

Getting an understanding of commonalities in early gambling experiences, especially where it might be associated with risky or harmful gambling, could be extremely impactful for strengthening harm-reduction measures for various identified groups, or for targeting educational activities.

Research with a longitudinal aspect that establishes patterns in gambling behaviour over time would aid our understanding of this theme, as would linked operator data with a focus on younger gamblers for the exploration of patterns in remote, regulated gambling.

Example research questions within this theme

These are the type of questions that could be considered in relation to this theme:

- What prompts different people to start gambling?

- How does gambling behaviour change over time as children become young people and young adults?

- What is the impact of major betting events, such as the World Cup or Grand National, on new gamblers?

Progress made in year one

The Gambling Commission published its Young People and Gambling 2023 report, which included data from both 17 year olds and pupils from independent schools for the first time.

We published insights from our Consumer Voice programme, which explored the impact of the 2022 World Cup on adults’ attitudes and gambling behaviours and the extent to which the tournament was a ‘gateway activity’ for new gamblers.

YGAM published their 2024 Annual Student Gambling Survey (opens in new tab) (PDF), investigating student gambling behaviour and its effects.

Forward look

We will be continuing to strengthen our research focus on children and young people by conducting qualitative research to build our understanding of: how young people are introduced to gambling, how they interact with gambling activities and the impact that gambling can have on their daily lives. The research will also explore experiences of activities akin to gambling. This will include exploring the occurrence of young people paying for loot boxes and in-game items, as well as exploring their use of social-betting apps.

We will also be continuing our work around gateway events, including tracking consumer behaviour during the Euro 2024 tournament.

We are exploring what useful information can be obtained from gambling live streams on streaming platforms such as Twitch and Kick, to get an idea of exposure to younger audiences.

Notes

3 Neurodevelopment, impulsivity, and adolescent gambling (opens in new tab), R A Chambers and Marc N Potenza, Journal of Gambling Studies, volume 19, 2003, pages 53 to 84.

4 Childhood use of coin pusher and crane grab machines, and adult gambling: A conceptual replication of Newall et al. (2021) (opens in new tab), A Parrado-González and P W Newall, Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2023.

5 Video game loot boxes are linked to problem gambling: Results of a large-scale survey (opens in new tab), D Zendle and P Cairns, PloS one, 13(11), e0206767, 2018.

6 What is the evidence that advertising policies could have an impact on gambling-related harms? A systematic umbrella review of the literature (opens in new tab), E McGrane, H Wardle, M Clowes, L Blank, R Pryce, M Field and E Goyder, Public Health, 2023.

7 Gambling and problem gambling among young adults: Insights from a longitudinal study of parents and children (opens in new tab) (PDF), D Forrest and I G McHale, report for GambleAware, 2018.

8 A longitudinal study of gambling in late adolescence and early adulthood: Follow-up assessment at 24 years (opens in new tab) (PDF), A Emond, M D Griffiths and L Hollén, report for GambleAware, 2019.

Evidence theme 2 - The range and variability of gambling experiences

Evidence theme 2 - The range and variability of gambling experiences

This theme is about:

- understanding the different experiences that people have with gambling – every gambler is different

- acknowledging how gambling fits into people’s lives and overlaps with other behaviours and experiences

- exploring consumer journeys and motivations

- how gambling habits and behaviours change over time.

Gambling participation figures estimate that up to 23 million people engaged in some form of gambling activity in the last four weeks. The majority of these people gamble without experiencing harms. Our research to understand why people gamble found that most people gamble to win money and that enjoyment is prevalent, but secondary to this.

Our role as a regulator is to license and regulate the gambling industry, and this includes a requirement to protect children and vulnerable people from being harmed by gambling. The focus of a large proportion of the research into gambling activities has been on those experiencing gambling-related harms, and the need for ongoing research in these areas is reflected in some of the other themes. Within this theme, we highlight the need to better understand the range of gambling experiences, including positive experiences of gambling.

Previous Commission research has identified gambling typologies and the Path to Play which helps to highlight the range of influences – but they also highlight that gambling experiences are not the same for all people. It is important to continue to build on this model to understand policy interventions at different steps along this path by hearing from a range of voices. We know that people move in and out of gambling-related harm (discussed further as part of the gateway products theme), but it may be helpful to know more about the range and variability of experiences, how they contribute to harmful gambling behaviours and any common indicators that could help others.

It is also valuable to understand the aspects of gambling that can be improved from a regulatory perspective, to ensure that gambling remains fair and open for everyone. This could include identification and consideration of the ‘average’ consumer, and their views and priorities on various topics, including – for example – their understanding of bonus offers and gambling products, and the role this plays in making informed choices.

There are a wide range of potential questions within this theme, and it’s likely that it will need a mixture of data sources to explore them, with qualitative research necessary to understand gambling experiences and quantitative research to better understand the scale of those experiences. Access to a wide range of anonymised datasets could offer the opportunity to see accurate play information and interaction between products within a gambling operator.

Example research questions within this theme

These are the type of questions that could be considered in relation to this theme:

- What do we know about the spectrum of gambling activity and what constitutes 'safe' gambling?

- How does gambling fit into a people's wider online activity or life?

- How and why do people’s gambling habits and behaviours change over time?

Progress made in year one

We published findings from two longitudinal studies completed as part of our Consumer Voice research programme, looking at changes in gambling behaviour during the 2022 football World Cup, and during a period of increasing cost of living.

Our collaboration with academics at Warwick Business School has started to use open banking data to explore consumer gambling spend over time and build a picture of how gambling fits into people’s lives.

Forward look

The Gambling Commission will release the first annual publication of the GSGB in July 2024, which will include findings on motivations for and enjoyment of gambling. We will also be assessing the feasibility and potential approaches to recontacting GSGB respondents to take part in longitudinal research

We are working on new research exploring the drivers of consumer trust and developing new survey questions to be added to the GSGB, allowing us to more effectively measure levels of trust in the gambling sector

We will be scoping new research exploring the consumer journeys and experiences of consumers who gamble in person, and how they choose to interact with both land-based and online gambling. New opportunities to look at real time data as well as self-reported data will bring greater insights.

Evidence theme 3 - Gambling-related harms and vulnerability

Evidence theme 3 - Gambling-related harms and vulnerability

This theme is about:

- gaining a better understanding of the different ways that consumers can experience harms

- being able to identify these consumers who may be more vulnerable or at risk of experiencing harms.

It is one of the Gambling Commission’s three licensing objectives to protect children and other vulnerable persons from being harmed or exploited by gambling and this has been at the heart of many regulatory changes in recent years, informed by a wealth of research on the topic. However, even defining vulnerability can be challenging, as a consumer’s vulnerability is not necessarily static.

The Commission has a commitment to collect robust, timely insights for a range of gambling behaviours, including the extent to which gambling harms are experienced. The range of gambling experiences and product risks are considered in different themes. There are many more situational and demographic factors linked to gambling-related harms, as well as evidence of inequalities in the way that harms are experienced. This warrants more in-depth research requiring different research tools and partnerships with other agencies that may inform policies for the prevention of harms.

Early gambling experiences are considered in evidence theme 1 but, among adults, research has shown links between gambling and harms such as financial losses and bankruptcy9, anxiety and depression10, and intimate partner violence11 and others. At its most extreme, gambling-related harms have been linked with increased suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and completed suicides.12 We need to continue to build high quality evidence , gathered within Great Britain, to establish whether and to what extent we can make causational links between gambling and severe harms.

Similarly, factors that increase an individual’s vulnerability to gambling-related harm have been identified as including events which can happen to anybody at any stage of life, including bereavement, relationship breakdown, poor health and impulsivity 13. A greater understanding of the impact of these factors and how best to offer timely protections against increased risks is important for all who are involved in this sector.

Other demographic characteristics of interest that may be experiencing harm in a different manner include gender, age and socio-economic groups. Other factors that remain under-researched in relation to their association with gambling-related harms include marginalised and under-represented groups, those with neurodiversities (such as autism or ADHD) and the experiences of different ethnic groups. As well as harms experienced people's own gambling, more needs to be done to understand the impact on families and friends of people who gamble, former gamblers who are still impacted by the consequences of their gambling and still remain exposed to gambling advertising, and society as a whole.

This theme, perhaps more than any of the others, has the widest range of potential questions associated with it, and this synopsis is far from exhaustive. Even with a period of three years, it will take significant resources to investigate many of these sub-topics and it is likely to require a blend of evidence from longitudinal, co-produced research with people with lived experience of gambling-related harms, account data and in-depth qualitative sources to gain a better understanding.

Example research questions within this theme

These are the type of questions that could be considered in relation to this theme:

- Which individual circumstances (situational or related to demographics) increase vulnerability to gambling-related harms?

- What’s the relationship between gambling-related harms and different co-occurring conditions?

- What are the experiences of people affected by someone else’s gambling?

- What early interventions are effective in reducing gambling-related harms?

Evidence theme 3 - Progress made in year one

The Gambling Commission completed the development of new survey questions on the consequences of gambling and gambling harms on people who gamble, and people who are affected by someone else’s gambling.

GambleAware have published several studies exploring the impact of gambling on minority communities , and secondary analysis of their Treatment and Support Survey exploring the relationship between mental health and gambling harms.

The Behavioural Insights Team have been conducting a number of studies assessing the effectiveness of a range of interventions on reducing gambling harms.

Forward look

Headline findings on the consequences of gambling for people who gamble, and people affected by someone else’s gambling. This will include data from the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) and new questions on the consequences of gambling, will be published in the first annual publication of the GSGB in July 2024.

We are conducting secondary analysis on the longitudinal data collected in our Consumer Voice research exploring the impact of increases in the cost of living on gambling behaviour, to explore whether and how participants’ PGSI scores change over a short period of time.

Important research is underway by academics at the University of Lincoln to conduct a psychological autopsy study to examine the events and circumstances leading to gambling-related suicide, alongside other studies funded as part of combined report for 2016 (opens in new tab) funded by Greo.

Notes

9 Gambling-related harms evidence review: an abbreviated systematic review of harms (opens in new tab) (PDF), Public Health England, 2021.

10 The impact of gambling on depression: New evidence from England and Scotland (opens in new tab), Sefa A Churchill and L Farrell, Economic Modelling, volume 68, 2018, pages 475 to 483.

11 Intimate partner violence in treatment seeking problem gamblers (opens in new tab), Amanda Roberts, Stephen Sharman, Jason Landon, Sean Cowlishaw, Raegan Murphy, Stephanie Meleck and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, Journal of Family Violence, volume 35, 2020, pages 65 to 72.

12 Problem gambling and suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm in England: evidence from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007 (report 1) (opens in new tab) (PDF), H Wardle, S Dymond, A John, S McManus, report prepared for GambleAware, 2019.

13 Gambling-related harms evidence review: risk factors (opens in new tab) (PDF), Public Health England, 2021.

Evidence theme 4 - The impact of operator practices

Evidence theme 4 - The impact of operator practices

This theme is about:

- understanding how common operator practices influence consumer behaviour

- assessing the effectiveness of interventions designed to detect and reduce gambling harms.

Gambling operators – along with gamblers and the gambling product – are part of the trio which make up gambling experiences. They have a significant ability to influence gambling activity through the environment that they provide and their behaviours.

Although operators are reliant upon their customers for revenue, they are also obligated to protect their customers from harm through regulatory requirements such as customer interaction requirements - and the largest gambling industry trade bodies have also made harm reduction commitments. Given the inherently risky nature of gambling, and the unusual adversarial relationship between gambler and operator, our research into exploring the information needs of consumers suggests that gamblers feel a tension around trust which risks undermining safer gambling messages.

Operator practices that impact upon consumers can include communications that encourage gambling such as advertising that is visible to everyone and targeted marketing to selected groups. It also includes communications that encourage gambling mitigation through the provision of tools and safer gambling messaging, whether targeted or otherwise and conducted through a range of different channels.

Other practices that could be considered include the presentation of information about products or offers, the way that a product or game functions and the location of gambling opportunities in-person or through online choice architecture. Remote operators often rely upon harm detection algorithms to identify consumers at increased risk of experiencing harms, and the effectiveness of these algorithms is also a topic of interest.

Amongst operator practices that are visible universally, research has examined the relationship between operator advertising practices, consumer awareness and consumer activity.14 There is the potential to understand more about directed advertising practices, how they fit into a complex online advertising ecosystem and their potential impact on selected groups. A particular group of interest are people living in disadvantaged communities who are more likely to be in the vicinity of land-based gambling premises15 and whether there is a link with other demographic characteristics identified in the previous theme as being associated with an increased risk of experiencing harms. Better understanding of the impact of advertising on children and young people is also important.

Regarding the more direct relationship, rules relating to VIP schemes were strengthened in 2020 and a significant reduction of consumers considered to be VIPs was reported by one industry body following the publication of their code of conduct.16 For telephone contact, there is indicative evidence of telephone calls to gamblers providing a positive impact on subsequent gambling activity17, including high-spending gamblers18. However, there are still a lot of unknowns regarding the impact on subsequent experience of harms and of safer gambling messaging on different groups of people. Methods of increasing uptake of safer gambling tools have been identified19 but the subsequent impact of doing so remains unclear and it is uncertain whether behaviours observed in jurisdictions with few regulated operators would be replicated in Great Britain.

To feed into harm-detection algorithms, research has been conducted that seeks to identify potential indicators of higher-risk gambling20 and it remains an area of great interest and debate, with differences between products, platforms and the amount of gambling activities likely. An improved understanding of the customer journeys that once seemed on a trajectory towards more harmful activity but did not progress to that level could be insightful in identifying protective operator practices. An additional unknown relates to the varying implementation approaches for algorithms, machine learning, artificial intelligence or other technological solutions applied by operators.

To explore this research theme, blending multiple sources of data is likely to be required, including operator-held account-level data suitable for detailed analysis, financial data, qualitative data, and potentially longitudinal data.

Example research questions within this theme

These are the type of questions that could be considered in relation to this theme:

- How can marketing and safer gambling practices be incorporated effectively together as part of a seamless player experience?

- How well do consumers understand information (for example, about offers or products) provided to them by operators?

- How effective are harm detection algorithms used by online operators?

- What are the factors that drive and influence consumer's perception of whether gambling is fair and can be trusted?

Evidence theme 4 - Progress made in year one

The Gambling Commission published new research exploring how gambling consumers engage with bonus offers and incentives, and the role that they play in the consumer journey, addressing evidence gaps outlined in our advice informing the Gambling Act review.

We also published research in support of our consultation on financial vulnerability and financial risk checks, which used a deliberative approach to enable participants to reflect upon the proposed policies in an environment free from media influence where information could be explained and explored.

Our Data Innovation Hub conducted pilot sprint projects exploring how to make best use of open-source data from Meta and Twitter to further understand marketing and advertising practices.

The Behavioural Insights Team have conducted several experiments testing different designs of game features, advertising and spending limits to isolate effective interventions for safer gambling.

Forward look

Upcoming research being conducted as part of our Consumer Voice programme will explore consumer trust in the gambling industry and the effect that operator practices have on this.

We are designing a pilot of industry data collection of a more detailed daily dataset (Regular Feed of Operator Core Data – ROCD) from a small number of operators, which if successful would enable us to conduct more in depth analyses of consumer play data to explore the impact of a range of factors on gambling behaviour.

Last year we published the outcome of a consultation on the frequency at which regulatory returns should be submitted by operators. As a result, from July 2024 all operators have moved to quarterly regulatory return submissions, with harmonised reporting periods. This will provide a deeper, more timely, more accurate understanding of the gambling sector.

We will continue the work started in the pilot data sprints, using the Meta ad library to track trends in gambling advertisements and expand the analysis to other social media platforms.

Notes

14The effect of gambling marketing and advertising on children, young people and vulnerable adults (opens in new tab) (PDF), Ipsos MORI, 2020.

15Geography of gambling premises (opens in new tab) (PDF), J Evans and K Cross, University of Bristol, 2021.

16BGC welcomes new rules on VIP schemes (opens in new tab), Betting and Gaming Council, 2020.

17Patterns of Play Technical Report 2: Account Data Stage (opens in new tab) (PDF), D Forrest and I McHale, NatCen, 2022.

18Reaching out to big losers: Exploring intervention effects using individualized follow-up (opens in new tab), J Jonsson, I Munck, D Hodgins and P Carlbring, Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 2023.

19Can behavioural insights be used to reduce risky play in online environments? (opens in new tab) (PDF), The Behavioural Insights Team, 2018.

Safer Gambling Messaging Project Phase Two An impact evaluation from the Behavioural Insights Team (opens in new tab) (PDF), report commissioned by GambleAware and completed by the Behavioural Insights Team.

20Examples include: Using artificial intelligence algorithms to predict self-reported problem gambling with account-based player data in an online casino setting (opens in new tab), M Auer and M D. Griffiths, Journal of Gambling Studies, 2022.

Predicting online gambling self-exclusion: An analysis of the performance of supervised machine learning models (opens in new tab), C Percy, M França, S Dragičević and A d’Avila Garcez, International Gambling Studies, Volume 16, 2016, pages 193 to 210.

Evidence theme 5 - Product characteristics and risk

Evidence theme 5 - Product characteristics and risk

This theme is about:

- improving our understanding of which products and behaviours carry greater risk of harm, for whom, and why

- gaining a deeper understanding of how consumers interact with different products and links to gambling harms

- identifying areas of new or emerging risk and building a strong understanding of changes in the market.

Gambling risk is formed from many factors that are integral to the gambling experience, these include the gambling product, place, and provider. The gambling product is often the most complex element of this trio, with many structural characteristics being combined into a single product which can add or mitigate riskiness for different types of gamblers. The complexity of some products can make it difficult to isolate the impacts of its individual structural characteristics, which therefore makes it difficult assess the product’s composite level of risk.

However, research has been conducted into characteristics of gaming products such as slots games, identifying factors such as frequency, audio-visual factors, rewards and information provision21. Tools have been developed on the basis of this research, which can assess the risk of gambling products, and have been used to identify additional characteristics. Consideration has also been given to the structural characteristics of sports betting products22.

A further complexity arises when considering the way in which individuals interact with different gambling products at different times, and how well they understand the products, as well as concepts such as probability and randomness. The ability to make informed choices is relevant to the Commission’s ’fair and open’ licensing objective (opens in new tab) (PDF), which is one reason why the focus on products needs to be considered alongside the other themes rather than in isolation.

The existing research has led to regulatory developments that include the long-standing requirements in the remote gambling and software technical standards (updated over time) for remote products, and reductions in the maximum stake levels for B2 gaming machines23 and scratchcards24. They also informed the changes to online slots games that impact the speed-of-play, illusion of control and removal of losses-disguised-as-wins.

There is no single homogenous gambling journey. This is why further research is required to establish the connection between product characteristics and increased risk of experiencing gambling-related harms. Research that identifies markers of harm and increased risk is important and can be utilised to develop appropriate mitigation methods. Examples of this type of research could include examining real-time account activity data, especially when combined with survey data in the manner of NatCen’s Patterns of Play research (opens in new tab) (PDF), opportunities created through data linkage, or robustly evaluated product trials in live environments.

Example research questions within this theme

These are the type of questions that could be considered in relation to this theme:

- Are certain product characteristics associated with gambling-related harms?

- Do some product characteristics disproportionately affect certain types of gamblers?

- How can gambling products be designed to mitigate the riskiness of game characteristics without compromising enjoyment?

- How do people’s patterns of play vary between products?

Evidence theme 5 - Progress made in year one

The Gambling Commission published an assessment of the impact of changes made to the design of online slot games, which showed a reduction in play intensity and no increase in staking activity.

Our development of the Gambling Survey for Great Britain (GSGB) involved extensive work to improve and test a new list of gambling activities asked as part of the core participations questions, to give a more up to date list of activities which better reflects the current market.

Research comparing risk levels between different types of online gambling products using behavioural markers of harm was conducted by the University of Adelaide, Sophro Ltd and the Kindred Group.

Forward look

The new activity list in the GSGB will allow for more accurate and relevant analyses on the relationship between gambling activities and a range of key factors, including PGSI scores, motivations, and the impacts of gambling.

We are designing a pilot of industry data collection of a more detailed daily dataset (Regular Feed of Operator Core Data – ROCD) which if successful, would enable us to conduct more in-depth analyses of consumer play data to explore play behaviours across different products and activities

Innovative research is taking place at Kings College London, using virtual reality to explore the interaction between product, person, and environment.

Notes

21Key issues in product-based harm minimisation: Examining theory, evidence and policy issues relevant in Great Britain (opens in new tab), J Parke, A Parke and A Blaszczynski, 2016.

22Structural characteristics of fixed-odds sports betting products (opens in new tab), P W Newall, A Russell and N Hing, Journal of Behavioral Addictions, Volume 10, Issue 3, pages 371 to 380.

23Government to cut Fixed Odds Betting Terminals maximum stake from £100 to £2 (opens in new tab), Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 2018.

24Rationale for agreeing the withdrawal of £10 scratchcard games, Gambling Commission, 2022.

Evidence theme 6 - Illegal gambling and crime

Evidence theme 6 - Illegal gambling and crime

This theme is about:

- understanding how gambling is linked to criminal activity

- understanding crime as a dimension of gambling-related harm

- improving our knowledge of the extent and impact of the unregulated market.

One of the Gambling Commission’s three Gambling Act licensing objectives (opens in new tab) is to prevent gambling from being a source of crime or disorder, being associated with crime or disorder, or being used to support crime. This can relate to crimes committed in connection with gambling activities (whether unlicensed, illegal gambling or funding gambling through crime), crimes that affect society or gambling operators, crimes committed by gambling operators, or connections between gambling and the criminal justice system.

Research by the Howard League has found links between high risk gambling and crime, including financial crimes25. A Swedish study found that fraud and embezzlement were the most common crimes to go to court.26 Other crimes are addressed through the Commission’s clear anti-money laundering rules for regulated operators, assessment and updates of the risks of different gambling sectors27 and the work of the Sports Betting Intelligence Unit to deal with reports of betting-related corruption and protect the integrity of sports and betting.

However, establishing causality for individual crimes can be difficult when there are many contributory factors or when solely correlational data is available. There is likely to be a sizeable impact upon others (particularly direct victims) as a result of criminal activity. Establishing the scale of this is particularly difficult when acquisitive crimes against friends or family may go entirely unreported. Some police forces have trialled screening for gambling addiction28 and that is being extended to more areas in 2024 to 202529, which has the potential to provide greater insights.

We are also interested in the extent and impact of the illegal gambling market in Great Britain. Research into channelisation has been conducted in other nations but further research is required to confidently estimate the extent of illegal gambling within Great Britain, who is engaging with it, and the impact that it is having. It is also important for the safeguarding of consumers to get an understanding of their recognition of when they are gambling with a company licensed in Great Britain and when they are gambling on the illegal, unlicensed market. We also need to understand why consumers are doing so, and consider the risks and impact of forms of gambling created by newer technologies, such as gambling with cryptocurrencies30.

As well as the research being done with those entering the criminal justice system, the extent of gambling within prisons has been unknown in Great Britain due to official participation surveys requiring postal addresses. There are reports of gambling being prevalent whilst incarcerated31 and a recommendation for greater support for many upon release.

Given the secretive nature of criminal activity, research into this theme may need more specialised and focused research methods, with greater reliance upon new and existing partner organisations and new tracking techniques identified within the gambling landscape section.

Example research questions within this theme

These are the type of questions that could be considered in relation to this theme:

- What is the extent of criminal activity occurring to fund gambling activities?

- What is the size of the illegal market, and what is the impact on British consumers?

- Which populations are particularly drawn to using illegal sites?

- What is motivating consumers to gamble on the illegal market?

- How easy is it for consumers to know that they are using an unregulated operator?

Evidence theme 4 - Progress made in year one

The Gambling Commission and its Digital Advisory Panel (DAP) conducted a project to explore how it can improve its understanding of the make-up of the illegal online market, its size and how it changes over time. This involved mapping the potential motivations for consumers using unlicensed gambling sites

We also started using Google search API data and web-scraping techniques to build the first iteration of a dwell time model for unlicensed gambling websites. This will feed into a dashboard tracking traffic to these sites over time to support and evaluate the Commission’s disruption work.

Forward look

We are undertaking research as part of our Consumer Voice programme to build on the work already conducted by DAP, by exploring consumers’ pathways into the illegal online market, motivations for using it, and awareness of licensed and unlicensed gambling. Academics at the University of Glasgow are also developing survey questions exploring participation in the illegal online market, with learning being shared between the two projects.

We will be collecting more robust data via the GSGB on the extent to which participants self-report having committed a crime to finance their gambling or to pay their own or someone else’s gambling debts, as part of our work to better understand the consequences of gambling.

We will continue to develop and refine the dwell time model, to increase the accuracy of the illegal online market size estimation, as well as incorporate more data sources into the dashboard, such as information from social media and streaming platforms like Twitch and Kick.

Notes

25Crime and Problem Gambling: A Research Landscape (opens in new tab) (PDF), S. Ramanauskas, Prepared for the Howard League’s Commission on Crime and Problem Gambling, 2020.

26Criminogenic problem gambling: a study of verdicts by Swedish courts (opens in new tab), P Binde, J Cisneros Örnberg and D Forsström, International Gambling Studies, volume 22, issue 3, 2022, pages 344 to 364.

27Such as: The money laundering and terrorist financing risks within the British Gambling industry 2020 and the updates relating to Emerging money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

28Arresting Problem Gambling in the UK Criminal Justice System: Raising Awareness and Screening for Problem Gambling at the Point of Arrest (opens in new tab) (PDF), GamCare and Beacon Counselling Trust, 2017.

29Police in England and Wales to screen suspects for signs gambling addiction is driving crime (opens in new tab), The Guardian, 2022.

30Safer gambling and consumer protection failings among 40 frequently visited cryptocurrency-based online gambling operators (opens in new tab), M Andrade, S Sharman, L Y Xiao, P W S Newall, Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, volume 37, issue 3, 2023.

31Gambling and crime: An exploration of gambling availability and culture in an English prison (opens in new tab), L R Smith, S Sharman, A Roberts, Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, volume 32, issue 6, 2022.

Our role in delivery

Whilst our six evidence themes cover a broad and diverse range of topics and issues, we are aware that there are key principles that should be inherent in the delivery of robust, good quality evidence across the wider ecosystem. These principles apply to the collection and development of evidence, and the communication and dissemination of the evidence base. We will continue our efforts to strengthen our approach to these principles over the course of the next three years.

Evaluation

As a regulator, one of our key areas of interest is in what works, for whom, and why. This relates to both evaluating the effectiveness of our own work and efforts to meet our licensing objectives, and also to the part that evaluation in the wider evidence ecosystem plays in improving our understanding and informing regulation.

There is a collective need for a better understanding of the impact of interventions and programmes aiming to prevent or reduce harm, across all the themes and issues we have identified. We recognise however that there are challenges, not least in the complexity of the interventions that require evaluation and the contexts in which they occur.

There is also a need to be proportionate, and to consider how we can be pragmatic and realistic (both in terms of resource and time) in delivering good evaluations. However, an increase in the use of evaluative approaches to tackle some of the gaps we have identified will be pivotal in developing a richer and more informative evidence base.

The role of lived experience

An essential part of the evidence base is the direct input of people with lived experience of gambling harms. The Commission’s Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) provides us with advice and perspectives based on its members own experiences of a wide range of gambling harms.

We will be working with LEAP and the wider lived experience community going forward to get their input into the scoping and development of new research projects, as well as when we have emerging findings and data to explore. This will be hugely beneficial and will improve the quality of the research that we conduct and the insights that we can tap into. This will take place alongside our wider consumer voice research programme, which will ensure that the views of all gambling consumers are taken into account when developing our evidence base.

Governance and transparency

Strong research governance is vital in building a robust and impactful evidence base. As a body that commissions research it is important that we conduct work in a way that is authoritative and trusted, and we are committed to ensuring that our processes are in line with best practice.

When we collect data that is reported as official statistics, we follow the Code of Practice for Statistics (opens in new tab). This ensures that the statistics we provide meet the needs of all users, are produced, managed and published to high standards, and are well explained.

We also follow best practice standards when procuring and delivering our wider research programme, and going forward we will be paying even greater attention to the way that we conduct our work. This includes strengthening our peer review processes, ensuring that our approaches are ethically sound, and working with partners who have robust procedures in place.

Linked to research governance is the issue of transparency, and the expectation that high quality research and evidence is transparent about methodological and analytical approaches, provides full disclosure and discussion of limitations, and allows others to replicate the work themselves. The development of our six evidence themes is itself an effort to be transparent about what drives our thinking, and we will strive to increase the transparency of our work going forward.

Accessibility

Lastly, we also recognise the need for good research and evidence to be accessible to all. There are two facets to this:

- allowing greater access to our research and evidence by making datasets available for wider analysis

- making sure that all of our research outputs are accessible to all users and that everyone can access the same information regardless of barriers or ability.

We already make several of our research datasets available for wider use via the UK Data Archive, and will be continuing to upload raw data from our core research projects as and when this is available.

As a public sector body it is a legal requirement that our website meets accessibility requirements, and we have been working for some time on ensuring that this is the case – not least in our Statistics and Research Hub, which is where all of our research, data and evidence is published and stored. We require all of our research partners to provide accessible content and we will be continuing to develop accessible ways to share our work.

Monitoring and improving the evidence base

Given the breadth and diversity of the questions and themes we have identified, it is clear that what we have set out here is an aspirational programme. There are significant challenges with regard to making progress in an ethical, robust manner and with pace. Some of the work outlined here will take us, and others, time to develop and complete – but we are committed to playing our part in improving the evidence base.

Going forward we will be transparent about how the Commission is making progress on these themes, as we add further layers to our understanding. We will continue to assess the quality of the evidence base that we rely on, and when needed we will work flexibly to shift focus as our knowledge improves. There will be points where we need to stop, explain, and discuss what we have found with our stakeholders and colleagues in the wider ecosystem before moving on, whilst also listening carefully to the insights delivered by others. We want to encourage others to contribute through their own work and experiences, from whichever part of the ecosystem they are in.

The pace of progress will ultimately be dictated by the resource available. We have purposefully developed our evidence themes in a way that allows work to be scaled up or scaled down should our capacity change. It will also be driven by the wider ecosystem’s capacity to make the most of the data and resources available to it, and ability to work collaboratively to ensure that our collective knowledge is the true sum of what we separately know.